Syria's business elite embrace Sharaa, push for Caesar sanctions repeal

Amid lingering fears and ongoing sanctions, Syrians are beginning to see signs of recovery and a fragile new beginning.

DAMASCUS/TARTOUS/HOMS — In an airy apartment in Damascus’ upmarket Al Malki neighborhood, where Syria’s toppled dictator Bashar al-Assad once lived, Ghassan Sukr, an avuncular Sunni industrialist shod in Gucci slippers, is planted before the family piano. He brandishes a hardcover book.

It is an Arabic translation of “Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty,” which was published in 2013 and earned its co-authors, the Armenian Turkish economist Daron Acemoglu and political scientist James A. Robinson, the Nobel Prize for economics last year.

Syria’s new president, Ahmad al-Sharaa, “has to read it, and I want to give it to him in person,” the sexagenarian insisted. This is because Sukr desperately wants Sharaa, the former jihadi commander from a bourgeois Sunni family who seized power in December, to succeed.

Sukr, whose detergent factory was bombed by regime forces in 2013, believes that Sharaa has what it takes. “They have a new approach. They think out of the box,” Sukr said of Sharaa and his new market-friendly cabinet that was unveiled in March. “We have given him a line of credit. The world should give him a line of credit, remove sanctions,” Sukr told Al-Monitor.

With his anti-regime credentials duly established, Sukr was tapped in March as deputy head of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce, the oldest in the Arab world. He serves on a committee that's rewriting the country’s investment and income laws. It has had 15 meetings since May. International Monetary Fund and European Union advisers “are involved.”

“They listen, and if they think you have a better idea, they adjust,” Sukr said.

Western officials concur. “In January the ministries were empty. Since then they have brought in experienced personnel from Idlib, Gaziantep and beyond, who worked with NGOs throughout the war,” Marianne Ward, resident representative and country director for the United Nations’ World Food Program (WFP) in Syria, told Al-Monitor.

“Our relationship feels more like a partnership. The job has become easier,” Ward said. Filling international staff positions under the Assad regime “used to be like a chess game,” Ward added, due to concerns about the former government's reaction to candidates under consideration.

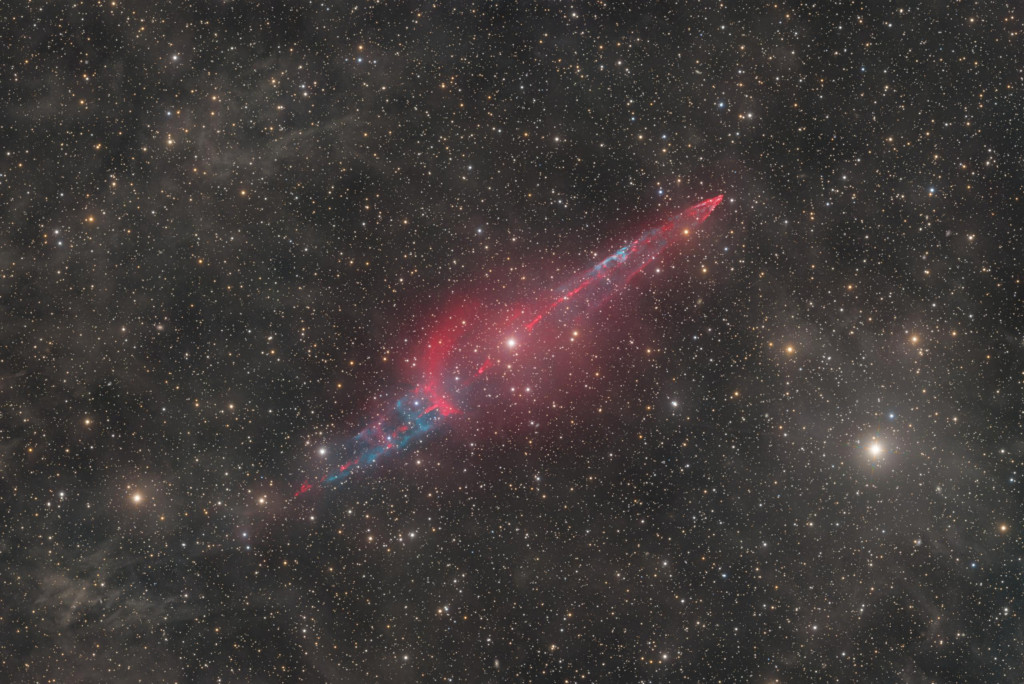

Scenes from central Homs. Oct. 8, 2025. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Dozens of business people, big and small, expressed similarly positive views in interviews conducted across three cities by Al-Monitor. Under the Assad regime, “possessing even one dollar was enough to get us to Saydnaya. Now we are free to carry dollars, to pay our staff in dollars,” said Mohammed Mhanna, who owns a chandelier factory in Qaboun, an industrial zone in Damascus that was flattened during the war. Mhanna was referring to the notorious prison where the Assad regime inflicted horrific abuses on tens of thousands of detainees. In the old days, he said, thuggish secret police would show up periodically at his factory in search of hidden dollars and to inspect his books. “In comparison to the old days, it is like paradise,” he said, blowing a kiss in the air.

Hasan Shbib, who exports men’s clothing to Africa, said that while business remains scant because of sanctions, “at least nobody can say we are a nation of drug dealers anymore.”

Shbib was referring to the Assad regime’s illegal multibillion-dollar amphetamine trade, which made Syria the world’s largest producer and exporter of Captagon. Shbib described how regime officials used to seek to forcibly stuff crates of Captagon among his clothes, leading him to abandon the business until Sharaa took over.

The new work ethic is palpable at Syria’s Jdeidet Yabous border crossing with Lebanon. Officials are all smiles as they process foreign and local travelers. The facilities are squeaky clean. Plastic tulips add a note of cheer. A new booth for “voluntary returns” — those who are moving back — has no takers.

Yet a steady trickle of Syrians from the diaspora is testing the waters. Muhammed Altawel, a Sunni consultant who lives in Saudi Arabia, is one of them. He has returned to his native Tartous to seek investment opportunities in real estate “and to help my country.” Altawel wanted to bid on a government tender to lease a state-owned hotel in the town of Mashtal Helou that was $200,000. “We asked for a five-year lease; the government would only give three. They are in a hurry for quick money,” he laughed.

In the religiously conservative city of Homs — a revolutionary stronghold that suffered years of heavy shelling, bombings and siege — support for Sharaa is sky high. Khaled Lababidi, who sells wedding gowns in the Homs souk, said business is picking up as refugees begin returning from Lebanon and Turkey, “but mostly from Turkey. I know 15 families who came from there.”

“Things are cheaper now,” he told Al-Monitor. A dress that used to cost 500,000 Syrian pounds now costs 300,000 because the Syrian pound has gained value since Assad’s ouster. “Sharaa is beautiful,” he said.

Men crafting chandeliers at a factory in Damascus, Syria, Oct. 6, 2025. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Amid all the ebullience, many acknowledge the enormity of the challenges facing the country after 60 years of ruthless dictatorship and more than a decade of conflict that has left more than 650,000 people dead, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a UK-based war monitor. An estimated 6.7 million Syrians are believed to have left the country. More than 13 million remain internally displaced. Around 85% of Syrians live below the poverty line. “It’s Gaza on steroids,” a Western diplomat speaking on background to Al-Monitor said of the level of destruction that has left vast swathes of the country in ruins.

One of the greatest obstacles to recovery is international sanctions, and another is the lack of security. This was on full display in July when government forces and members of the Druze minority clashed for days in the southern province of Suwayda. Abuses were committed by both sides, but the finger of blame was largely pointed at Sharaa for failing to rein in his men.

Footage of his soldiers committing atrocities against Druze civilians drew horror and condemnations from across the globe. Israeli airstrikes against Syrian forces in Suwayda, notionally in defense of the Druze, forced them to retreat. Further Israeli strikes on the Ministry of Defense in the heart of Damascus blew a giant hole in the building — and in Sharaa’s credibility. Pockets of Suwayda, including the city center, remain outside the central authorities’ control.

Sharaa’s standing had already been badly shaken by mass violence in March of this year by disparate groups, including foreign jihadists, Turkish-backed Sunni militias and government forces targeting the country’s Alawite minority along Syria’s Mediterranean coast. A government committee tasked with investigating the massacres found that at least 1,400 people, mostly civilians, had perished. Its own military leaders had not ordered the attacks, the government claimed.

Sporadic killings, abductions and rapes keep the population, especially minorities and the moneyed, on edge. On a recent evening, five scions of Damascus’ wealthiest families gathered at a cafe in Al Malki to talk about their hopes and their fears. They had decided to take security into their own hands. “We have our own neighborhood patrol, 35 of us with walkie-talkies and all,” said Tarek Jajeh, who imports luxury cars from the United States to the United Arab Emirates and eventually Syria.

Things began to improve, Jajeh said, about two months after a new director of internal security for Damascus, Osama Atika, was appointed in May.

Residents were rattled by the recent killing of a young man by an individual said to be a security guard from the presidential palace. “It was because he was wearing shorts,” said Mohammed Ibo, who owns a fruit juice factory in Qaboun. Authorities said the man was unhinged. “Then why did they give him a gun? Why was he even recruited?” Ibo asked. Over the past two months alone, five robberies have occurred in Qaboun, one at a factory that produces doors and is located very near Ibo's. It had been stripped of all its machinery. “When the owner went to the police, they told him, ‘Find the thieves, and we will get back your stuff,’” Ibo said.

“The security situation is the underpinning of the economic situation,” Ward said. And sanctions continue to “suck the oxygen out of the economy.” It’s something of a catch-22. The “revenge killings against minorities won’t finish until the economy gets better,” said Adham Massoud Kak, a Druze activist. And the economy can’t improve until international sanctions are fully lifted.

Jdeitat al-Fadl, a squalid suburb in southwest Damascus, teems with impoverished Palestinian refugees and internally displaced Syrians from across the country. Crime and drug abuse abounds. Visitors are cautioned to mind their belongings. Dozens of women and children queue in front of a government-run bakery that was rehabilitated with WFP support. The bakery offers a rare lifeline, selling subsidized bread.

Its manager, Mahmoud Zeitoun, says the facility produces 10,750 bags containing 12 pieces of flat Syrian bread per day, which are then sold for 4,000 Syrian pounds each. On the open market a bag containing nine pieces goes for double that price. The facility operates 24 hours a day, six days a week due to high demand. When it was launched in 2023, the bakery was open for a fraction of that time.

Residents in Damascus' Jdeitat al-Fadl neighborhood queue for subsidized bread, Oct. 7, 2025. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Amina is a 41-year-old tribal woman who came to Jdeitat al-Fadl from Al Bukamal on Syria’s border with Iraq in the early days of the conflict in 2012. She has nine children aged between 2 and 13. The family has not eaten any meat “for years.” “Some of my children never even tasted meat,” she said. Bread is their main staple, and the bread sold at the government bakery “tastes much better now,” she told Al-Monitor. Like many of the women and children here, she resells bread from the bakery at 6,000 pounds per bag. The 2,000 difference allows her to eke out around 45,000 pounds, or the equivalent of about three US dollars, on average per day.

Her life, and those of millions of Syrians, could change dramatically once sanctions are removed in their entirety.

Speaking in Washington this week as part of Syria’s first delegation to the World Bank’s semiannual gathering of Central Bank governors and finance ministers since the outbreak of civil conflict in 2011, the country’s finance minister, Mohammed Yisr Barnieh, said the country had the potential to “reach the level of Malaysia” in five years. Without international support from financial institutions, Syria “cannot move ahead,” Barnieh said. “But if you are slow, we will move without you.”

In fact, the EU has already scrapped most of its sanctions. The United States followed suit, following President Donald Trump’s groundbreaking May encounter with Sharaa in Riyadh.

But sanctions that were imposed by the US Congress in 2019 under the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act, or the Caesar Act, and effectively bar Syria from accessing the international banking system, remain intact. “This blocks everything. It's like a rope around our throats,” Ibo, the businessman, said.

Gulf states that are raring to aid Syria cannot do so as a result, leaving their multibillion-dollar pledges of investments on paper only.

“The moment you touch a US dollar, you fall under US jurisdiction, and the Caesar Act obviously applies. So given that Gulf banks use dollars in their banking system, they need to comply,” said Vittorio Maresca di Serracapriola, lead analyst for sanctions at Karam Shaar Advisory, a consultancy focusing on Syria’s economy. “Moreover, the Caesar Act is peculiar in itself because it imposes secondary sanctions” on non-US companies that do business with Syria, Serracapriola explained.

Like the Syrian government and its international allies, Serracapriola says Caesar sanctions are no longer legal because they were written to punish the now-defunct Assad regime.

The mood in the Congress — soured by the horrors in March and July — appears to be finally shifting. Sharaa’s victory lap at the 80th session of the United Nations General Assembly, where he rubbed elbows with world leaders, may have helped. So, too, has renewed dialogue with Kurdish leaders, brokered by Trump’s Syria envoy, Tom Barrack, to integrate their forces with the national army. The Syrian Kurds, whose valiance against the Islamic State has won them influential friends in the Congress, control nearly a third of the country, including most of its oil wealth.

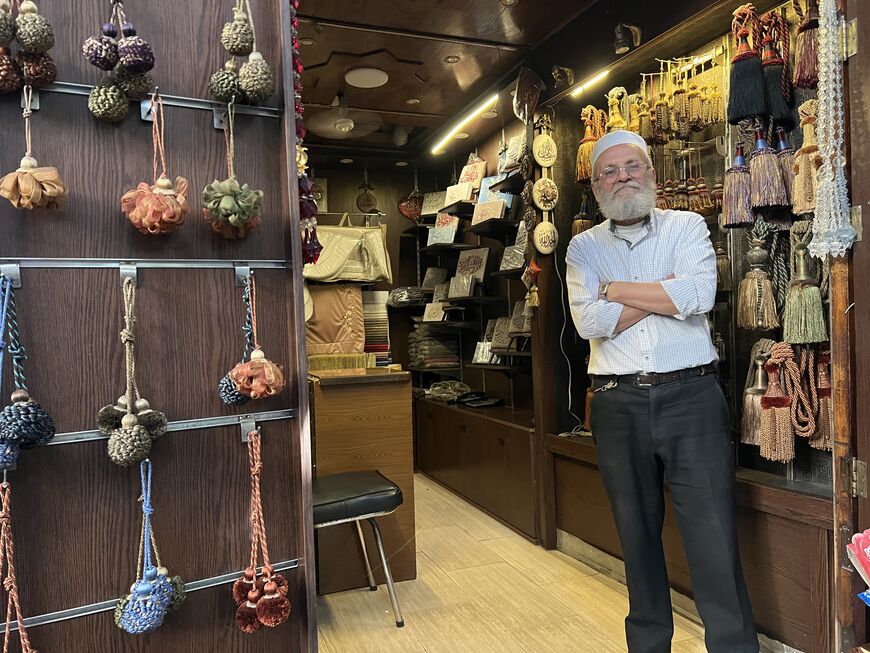

A tassel maker at Damascus’ souk says business is good but that his craft is dying, Oct. 6, 2025. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Meanwhile, this month’s parliamentary elections that were based on a convoluted indirect voting system rather than on universal suffrage have added a veneer of legitimacy to the new government despite yielding mostly Arab Sunni males.

On Oct. 9, the Senate approved the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for 2026. It included two amendments to the Caesar Act, one calling for a full repeal, another for a conditional repeal requiring the administration to submit regular reports on Syria’s conduct and allowing sanctions to snap back automatically if the government misbehaves. Given these developments, Serracapriola believes there is a greater likelihood that the Caesar Act could be finally scrapped, as it now “forms part of a must-pass bill rather than a stand-alone proposal.” However, the NDAA, and hence the repeals, will enter the committee stage, during which negotiators from the Senate and the House of Representatives must battle out their differences over their versions and present a unified text that needs to be approved by both chambers before going to the president for the final signature.

Until such time, businessmen like Mhanna continue to navigate their way through sanctions using third parties. Mhanna, for example, buys stock from China, gets his customers in Saudi Arabia to pay for it and then repays them with chandeliers. “It would be far cheaper and safer if I could settle the transaction directly,” he said. Annual production at the factory has gone down from 1,100 chandeliers to 300. Still, it’s a lot better than during Assad’s rule, when the amount of bribes doled out to customs officials and others meant that “if you ordered a box of crystals from Prague worth $10,000, by the time it was flown to Beirut, then crossed over land through multiple checkpoints, it ended up costing you double,” Mhanna said.

That is not to say that corruption has ended, many say. “But it’s mostly among older officials. Not the new ones,” said Kak, the Druze activist who was recently pressed for a bribe. “They are honest,” he said. “At least for now.”

[Source: Al-Monitor]