‘I made £1m in 90 days. It’s easy if you have no ethical boundaries’

Oobah Butler dived into the fast-cash trend and found a terrifying world of players with few scruples

If the endless array of books, podcasts, YouTube channels and online masterclasses touting get-rich-quick schemes is to be believed, becoming an overnight millionaire has never been easier.

This is the theory put to the test by British film-maker and trickster Oobah Butler in How I Made £1 Million In 90 Days, his latest documentary for Channel 4.

Disturbed by the rise of “hustle culture” – a movement targeted at young men that teaches relentless go-getting is the way to win – yet still seeking financial security himself in his mid-30s, Butler set out to see if buying into the mindset could land him a seven-figure fortune.

“Hustle culture sucks up so much oxygen because it’s sort of tantalising as a subject. A lot of our cultural diet is just talking about money,” he says.

“I wanted to see if it was possible to make money if you don’t have any ethical boundaries, if you just say yes to everything.”

Butler is no stranger to taking on unorthodox challenges.

In 2017, he managed to turn his garden shed into London’s top-rated restaurant on Tripadvisor to highlight the dangers of fake reviews. And in 2023, he called out Amazon’s tax avoidance by buying filler from the online marketplace to fill potholes, then sending the bags back filled with sand and claiming a refund. In other words, he forced Amazon to contribute to the infrastructure it benefited from.

But this latest stunt had a more personal edge. Without divulging much detail, Butler claims his parents lost money to a Ponzi-style scheme when he was younger. It left him painfully aware of the impact of chasing fast cash.

“I definitely have sympathy for people who have been sucked in, because it all just comes from a place of insecurity in terms of financial stability and identity,” Butler says.

Monetising the ‘attention economy’

For Butler’s challenge, he had to stay within the law, which meant avoiding anything that could be considered an out-and-out scam. So, after turning to the works of self-styled business gurus such as Diary of a CEO host Steven Bartlett and the real-life Wolf of Wall Street Jordan Belfort, Butler decided the best way to make quick cash was to monetise the “attention economy”.

This strategy is based on creating a buzz online and selling products or services off the back of it – something he says clothing companies and artists, such as Banksy, do particularly well.

Butler’s initial plan was to create the world’s first “ethical sweatshop” to manufacture football shirts designed and made by children. The presence of a TV crew provided a loophole that meant the children were classed as performers rather than workers, with the intention of creating an online sensation and cashing in accordingly.

Butler says the plan stemmed from his hustle culture research, which teaches that “it’s always better to p--s people off”. While the football shirts generated only £10,000 – 1pc of his seven-figure target – it highlighted how far he was willing to stretch these mantras.

He also tried launching his own educational masterclass and – in a scene that could be plucked from dystopian drama Black Mirror – auctioned 10pc of himself and his future earnings to a room full of millionaires, both with little success.

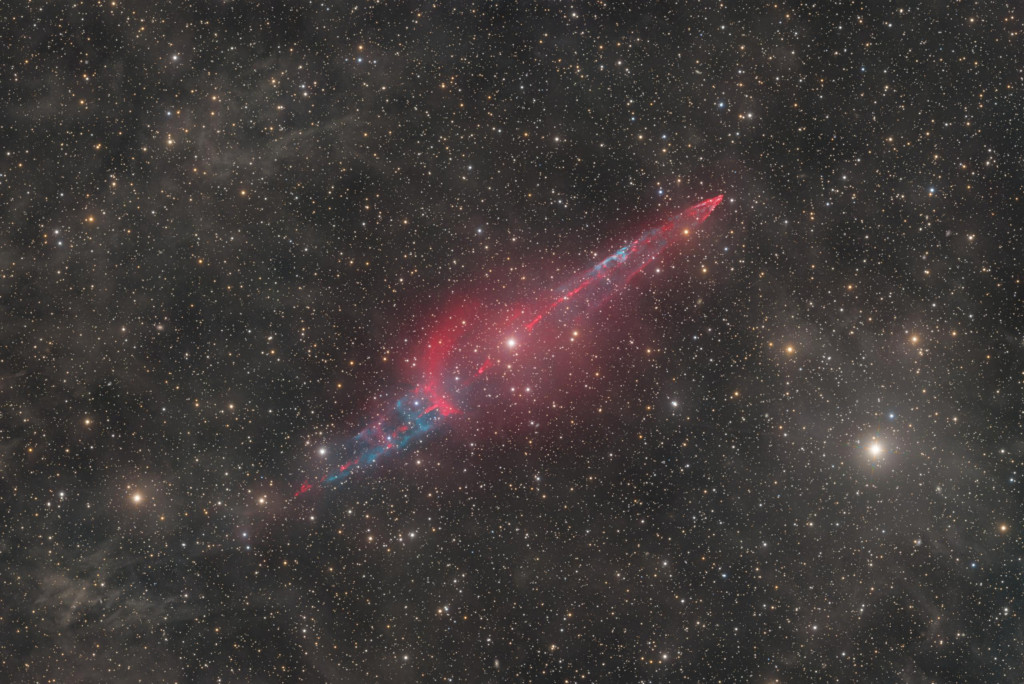

Venture into cryptocurrency

However, it was the “wild west” of cryptocurrency that Butler encountered his most unsettling – and most profitable – venture.

The documentary shows him travelling to New York to meet several high-net-worth individuals who made a windfall from crypto. While there, he finds the crypto system is a terrifyingly efficient way to capitalise on the attention economy.

Iqram Magdon-Ismail, the co-founder of digital payment app Venmo, introduced him to the world of meme coins – unregulated digital tokens known for being big but very risky money-spinners.

Meme coins act like other cryptocurrencies but hold little value and no real-world utility.

Early investors create hype around the token, driving its price up. When interest wanes, the stock is dumped, leaving late entrants out of pocket and others mindbogglingly rich.

The most well-known is Elon Musk’s favourite, Dogecoin, which has endured dizzying fluctuations between $0.74 (£0.55) and $0.00009 since launching in 2013. But even during the documentary’s filming, Magdon-Ismail claims to have made $250m from his own meme coin.

In the wake of the pandemic, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) warned of the dangers of crypto trading amid a proliferation of online influencers promoting it. But any meaningful crackdown remains elusive, particularly given that much of the trade is conducted in other countries.

Nikhil Rathi, the FCA boss, said the financial watchdog estimates “several million” people in the UK under the age of 35 have invested in digital assets without understanding the risks.

With his reputation as an internet prankster and someone who arguably built his own reputation on the back of the attention economy, Butler was told he could be a prime candidate to launch his own meme coin.

Multimillionaire crypto investor Kavita Gupta said that for 10pc of his future income, she would give him the £1m he was after, under the proviso that he release his own digital token.

At this point, viewers watch him struggle to weigh up whether to reject the money or become the sort of person who had tricked his parents.

“It’s always, ‘Well, okay, you can have the money, but you have to do something that you don’t feel comfortable with’. If you’re willing to f--k someone over, you can make your life a lot easier.”

By now, the question of the £1m had almost become irrelevant. Butler claims that the emotional and physical toll of relentlessly chasing money left him exhausted and downbeat. “There’s something in the indefatigable nature of these people that I obviously don’t have,” he admits.

It was in this state that his quest to discover whether get-rich-quick schemes held any answers for people reached its inevitable conclusion.

“If you look at hard numbers, I don’t think people are behaving better with their money,” Butler says. “I just think that they’re talking about it differently and talking about it more. And crucially, are they happier? I don’t know. It doesn’t feel like it, does it?”

[Source: Daily Telegraph]