PKK leader Ocalan appeals to Iraqi Kurdistan president for help in Turkey peace talks

The jailed PKK leader asks President Nechirvan Barzani to help advance negotiations aimed at ending decades of conflict with Turkey.

Abdullah Ocalan, jailed leader of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), has appealed directly to Nechirvan Barzani, president of Iraq’s Kurdistan Region, for help in ongoing talks with the Turkish government to end the more than 40-year conflict between his rebels and Ankara.

In a letter delivered to Barzani last week, Ocalan noted that the outcome of the talks would “inevitably affect Iraq and the Kurdistan Region. My aim in this process is to bring about a lasting solution based on democratic principles.”

“It is of great importance that you also take on leadership of the process,” Ocalan added, according to excerpts from the typewritten letter that were shared exclusively with Al-Monitor.

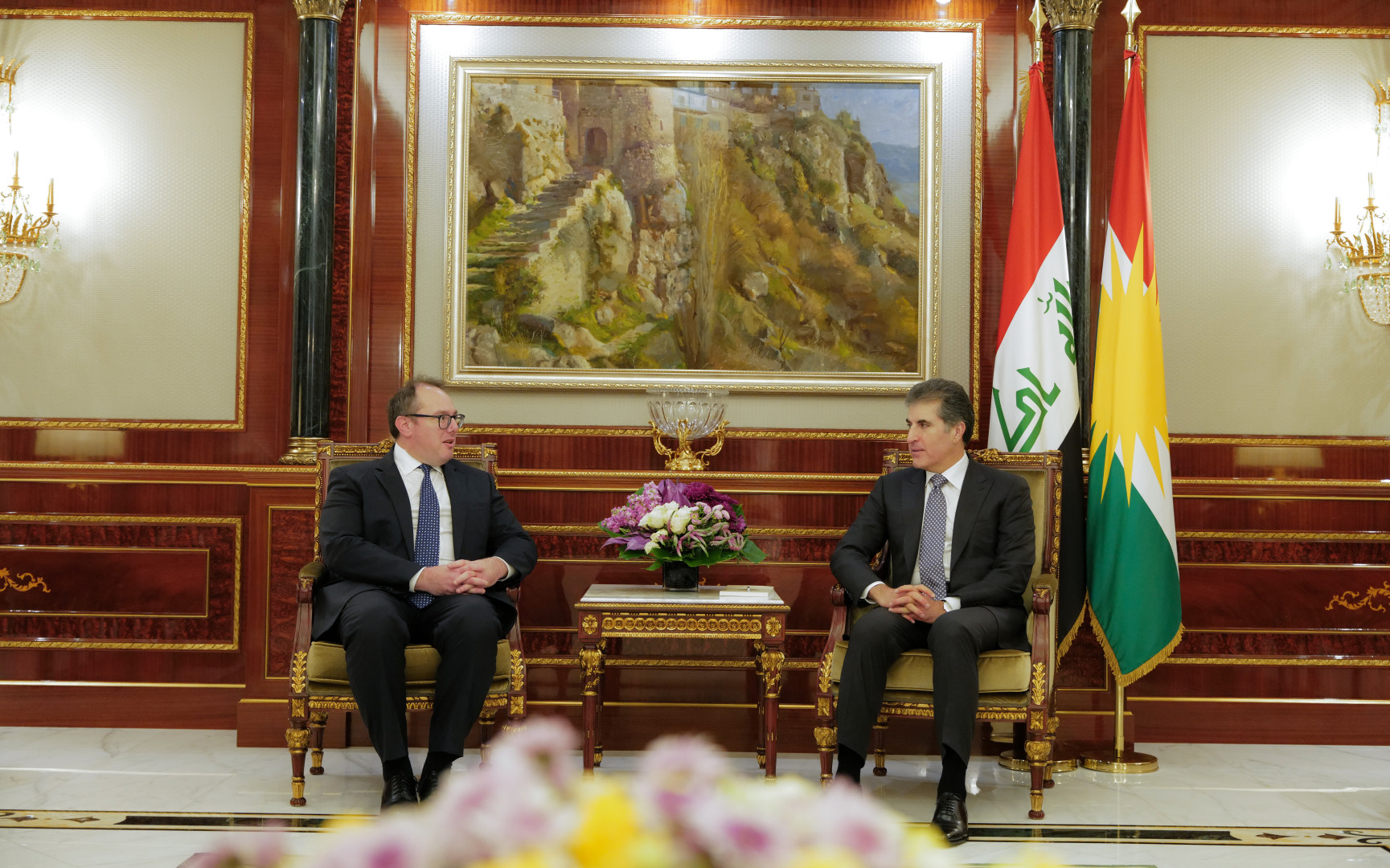

Ocalan’s plea from prison came amid mounting uncertainty over the future of the talks that were launched last year and coincided with Barzani’s meeting with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Ankara last week. In the hour-long meeting on Oct. 7, Barzani urged the Turkish president to use his influence to expedite the conclusion of a legal framework that would allow eligible PKK rebels holed up in the mountains of the Iraqi Kurdistan Region to return to Turkey, a senior Iraqi Kurdish official told Al-Monitor.

Yet, in public, Barzani has pointed the finger of blame at the PKK, accusing them a day after his meeting with Erdogan at a forum in Erbil of not complying with “president” Ocalan’s orders and of “playing games.” He did not elaborate. The PKK issued an angry rebuttal, calling Barzani’s words unacceptable. Barzani’s oblique endorsement of Ocalan reflects Ankara’s shifting rhetoric on the 76-year-old rebel leader.

Barzani, who has enjoyed exceptionally close relations with Erdogan for more than a decade, has emerged as an influential broker in Kurdish affairs. Last week, it was largely at his behest that Erdogan agreed to scrap a flight ban on Sulaimaniyah International Airport that was imposed in April 2023 on the grounds that it was being used as a logistics hub for the PKK. Sulaimaniyah is governed by the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, which is the junior partner in the Kurdistan Regional Government led by Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iraq. The PUK has traditionally aligned itself with Iran and is overtly sympathetic to the PKK. The KDP is Ankara’s top ally in Iraq and has played a key role in facilitating military operations against the PKK.

The flight ban led to significant economic losses for the Kurdistan Region, forcing the PUK to rely on Iran and Baghdad for air connections from Sulaimaniyah. Turkey’s decision to rescind the ban came just three days after it had extended it until January 2026.

“Barzani is the key actor in Turkey’s relations with the Kurdistan Regional Government, which are based on personal rather than institutional ties, and his constructive role in promoting peace between Turkey and the Kurds is undeniable. This has been proven once again,” Roj Girasun, cofounder of RAWEST, a research and polling outfit based in Turkey’s Kurdish-majority province of Diyarbakir, told Al-Monitor.

In 2017, when Iraq’s Kurds held their ill-fated referendum on independence, Baghdad slapped a flight ban on the entire Kurdish region. Turkey, Iran and the United States were viscerally opposed to the move. Yet, in a sure sign of his affection for Barzani, Erdogan overrode then-Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s protests against letting Barzani, who was the KRG prime minister at the time, cross overland to Turkey to attend meetings in Europe, a well-placed source familiar with the incident told Al-Monitor.

How these diplomatic successes will play domestically ahead of nationwide parliamentary elections that are due to be held on Nov. 11 in Iraq is another matter. "While the end of the ban is a welcome boost for the president, it is unlikely to translate into electoral gains for the KDP in Sulaimaniyah or elsewhere in Iraq during the November elections. To increase its parliamentary seats, Barzani's KDP would need to disrupt the entrenched electoral base and political map of Sulaimaniyah," Yerevan Saeed, an Iraqi Kurdish academic, told Al-Monitor. "So far, however, it has struggled to make inroads there due to the region’s distinct political history, which has also shaped its voting geography, Saeed said.

"For more than a decade, the PUK has faced leadership crises, internal divisions and factionalism. Yet the votes lost by the PUK have tended to shift to other parties rather than to the KDP," Saeed added.

It remains to be seen what impact Barzani will have on the pace of the negotiations between Turkey and its own Kurds. However, in a potentially significant development, Barzani met with the governor of Sirnak in Erbil on Monday. Sirnak, a Kurdish-majority province in southeastern Turkey bordering Iraqi Kurdistan and Syria, would be a natural route through which amnestied PKK fighters could be discreetly processed and allowed to return home, Ilhami Isik, a Kurdish commentator in Turkey who advised the government during a previous round of peace talks in 2013, told Al-Monitor.

Various forms of amnesty and other legal dispensations are at the center of Ankara’s latest attempt to end the PKK’s armed insurgency, a process Erdogan labels “terror-free Turkey.”

Yet no concrete progress has been achieved since Ocalan called on his guerrillas to abandon their armed campaign and disband in a Feb. 27 message that was shared with the public. In March, the PKK declared a ceasefire. In May, it announced the end of its armed campaign, launched in 1984 originally to establish an independent Kurdish state and later aimed at securing self-rule within Turkey.

However much the government strives to present the process as being solely focused on ending the conflict, expectations on both Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the pro-Kurdish DEM Party go well beyond that. Erdogan needs Kurdish support for constitutional and other measures that would allow him to run for a third presidential term and, most importantly, to win. The current constitution sets a two-term limit on the presidency. Elections are due to be held in 2028 at the latest, and Erdogan’s popularity continues to wane amid spiraling inflation.

The Kurds, for their part, want constitutional changes that would enshrine cultural and political freedoms and legal measures that would pave the way for freeing thousands of prisoners of conscience in Turkey. The case of Selahattin Demirtas, former head of the DEM Party's predecessor known as the Peoples' Democratic Party, is widely seen as a test of the government’s sincerity. He remains behind bars, despite a European Court of Human Rights ruling that his continued incarceration is unlawful.

The Kurds’ top ask, however, is that Ocalan be granted amnesty. That carrot was dangled a year ago by Erdogan’s far-right ally, Devlet Bahceli, when he told parliament that the PKK leader could launch his call for peace in person from the very same chamber. The trouble, however, is that Turkey’s demands don’t stop at its borders. It wants the PKK’s Syrian arm, known as the People’s Protection Units (YPG), to disarm and disband as well. The YPG forms the core of the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces, which also includes large numbers of Arab fighters.

According to leaked minutes of his meeting with DEM lawmakers, Ocalan called northeast Syria a red line, prompting speculation that he is leveraging his influence over the SDF — which has yet to be fully tested — to secure gains at home.

Turkey has long pressed for the SDF to be fully integrated into the national army being formed by Syria’s new government, led by President Ahmed al-Sharaa.

US Syria envoy Tom Barrack brought SDF commander-in-chief Mazlum Kobane and Sharaa together in Damascus on Oct. 7, in a bid to push both sides forward on a framework agreement they signed on March 10 to reintegrate the Kurdish-led northeast into government structures in Damascus.

Little progress has been achieved since then, and alarm bells were set off by fierce clashes earlier this month between government-supported forces in Aleppo and Kurdish fighters near the Kurdish-majority areas of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh. The meeting, also attended by CENTCOM commander Adm. Brad Cooper and Syria’s Defense Minister Murhaf Abu Qasra, resulted in a comprehensive ceasefire across all lines. On Monday, Kobane told France’s Agence France-Presse that a “preliminary agreement” had been reached with Damascus for the integration of his troops into Syria’s military and security forces. “The most important point is having reached a preliminary agreement regarding the mechanism for integrating the SDF and then [Kurdish] internal security forces within the framework of the defense and interior ministries,” Kobane said.

Kobane acknowledged, nonetheless, that the sides remained divided over the form of future governance, with the Kurds and other minority groups — most notably the Druze — pressing for decentralization. At the same think tank event where he had chastised the PKK, Barzani echoed Kobane’s view, saying he told Sharaa “clearly” when they met at a diplomatic forum hosted by Turkey in April that “a strong central system cannot work in Syria. The country must move toward a model that recognizes and empowers all communities.”

The senior Iraqi official briefing Al-Monitor said Barzani aired the very same views in his meeting with Erdogan.

[Source: Al-Monitor]