What the capture of Maduro means for China and Russia

The US’s strike on Caracas has sent out shockwaves felt in Moscow and Beijing. These are the implications

It was a made-for-Netflix moment, giving Donald Trump exactly the kind of attention-grabbing spectacle he craved.

Few observers believed the United States could pull off the surgical operation that succeeded in capturing and exfiltrating Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s president, and Cilia Flores, his wife.

In 1989, it took a fortnight for US troops invading Panama to locate, besiege and capture its strongman ruler Manuel Noriega – an operation that claimed 26 American lives and left hundreds of Panamanians dead. But Panama is a tiny country with a single large city, and the US already had a substantial military presence there.

Any operation in Venezuela, which is vastly larger and defended by a large army and loyalist militias, seemed more likely to echo the US invasion of Iraq, where it took nine months to track down Saddam Hussein, and regime change triggered chaos and bloodshed, badly staining Washington’s global reputation.

Yet, so far at least, Mr Trump has confounded his critics, pulling off – presumably with the collusion of at least one member of Mr Maduro’s inner circle – a spectacular operation more commonly associated with Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency.

The US president, in his own inimitable way, will rightly hail the success of a mission that effected the swiftest regime change operation of its kind in more than a century. He will also seek to present it as a muscle-flexing moment proving that the American Colossus still bestrides the globe.

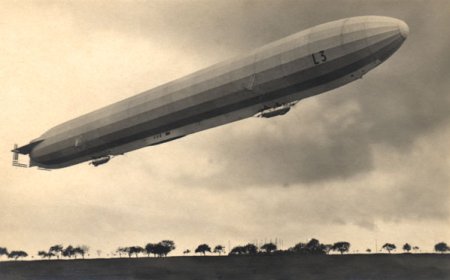

After all, only great imperial powers can engage in such gunboat diplomacy, toppling troublesome potentates with the same casualness the British Empire once rid itself of querulous Burmese kings or Punjabi maharajahs. It is even possible that the US operation in Caracas, the Venezuelan capital, surpassed Britain’s 38-minute war to topple the Sultan of Zanzibar in 1896.

By this reading, it is easy to imagine that the lightning raid in the Venezuelan capital has caused deep unease in Moscow and Beijing, Mr Maduro’s principal foreign backers. After all, the US has apparently just severed the chief South American tentacle of the global anti-US nexus with unexpected ease.

Certainly, no autocrat likes to see one of their own seized, shackled and renditioned – his fate left for a foreign court to decide.

Vladimir Putin was reportedly so disturbed by the lynching of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 – apparently imagining that the same fate could one day befall him – that he watched video footage of the killing on loop.

One can readily imagine the Russian leader, who has himself been indicted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes, feeling similarly disquieted by Maduro’s plight.

Yet these misgivings may not run as deep as some might assume.

There will certainly be those in Moscow and Beijing who conclude that the Caracas operation is further evidence that Mr Trump is more interested in projecting power regionally than globally – that he is, in other words, a backyard bully but a centre-stage coward.

So far, Mr Trump has shown himself willing to assert dominance in a widespread but limited fashion: launching sporadic, narrowly targeted air strikes against Isis affiliates in Nigeria, Houthi militants in Yemen, and mounting a spectacular but brief operation against Iran’s nuclear programme.

Such missions, critics note, appear at least partially designed to deliver a showbiz moment of victory that plays well with the president’s base.

The seizure of Mr Maduro is clearly a triumph that will gratify many on the US Right and deliver a chilling message to any South American leader tempted to step out of line. But the further out one zooms, the less impressive it arguably looks.

Mr Trump, advisers will be telling Putin and Xi Jinping, is clearly content to pick fights with weaker opponents. He has shown less appetite to stand up to Russia over Ukraine and has raised fears that he could abandon Taiwan in pursuit of a grand bargain with China.

In early December, the Trump administration published its National Security Strategy, a startling document that formally articulated a shift in US foreign policy towards a world view based on spheres of influence and “America First” transactionalism.

Should the Chinese and Russian leaders conclude that the seizure of Mr Maduro is part of the implementation of a strategy in which the US withdraws from a global role in pursuit of regional hegemony, they may feel emboldened rather than deterred – with potentially catastrophic consequences for international stability.

US officials would reject such an interpretation, arguing that only by re-establishing its pre-eminence in its own hemisphere can it reassert its global dominance.

Mauricio Claver-Carone, Mr Trump’s former envoy to Latin America, told the New York Times in November: “You can’t be the pre-eminent global power if you’re not the pre-eminent regional power.”

Whichever interpretation prevails, it is clear that the Western Hemisphere has once again become Washington’s central theatre abroad – even as traditional US adversaries have been given a freer hand elsewhere.

Since returning to power, Mr Trump has sought to reassert the 1823 Monroe Doctrine, a warning to outside powers to stay out of the Western hemisphere that later evolved into a belief in US hegemony over the Americas.

In fact, he has gone even further: laying claim to Canada as the 51st state, rebranding the Gulf of Mexico as the “Gulf of America” and demanding the handover of Greenland to the US.

As his first year in office wore on, he fleshed out what wags came to call the “Donroe Doctrine” to encompass regime change in Venezuela.

Shortly after his inauguration, Mr Trump signed an executive order designating the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua a “foreign terrorist organisation” as his administration laid the legal groundwork for a criminal indictment against Mr Maduro.

US officials claimed the Venezuelan president was conspiring to smuggle drugs into the US. Over the summer, the US bounty on Mr Maduro, stemming from “narcoterrorism” charges, was doubled.

The final piece of the legal case came in mid-November, when the administration announced it would designate the Cartel de los Soles, which it claimed Mr Maduro headed, a foreign terrorist organisation.

Not only was he, by Washington’s reckoning, a usurper who had stolen power at the ballot box, he was also a fugitive from the law. The case for seizing him – one questioned by critics inside and outside the US – had been made.

Analysts have long insisted that Mr Trump’s Venezuela policy had little to do with drugs. Most of the fentanyl driving America’s narcotics epidemic does not originate from Venezuela.

This was always about regime change – an objective championed in some political circles in Washington for more than a decade. Marco Rubio, the US secretary of state, pressed a hawkish Venezuela policy all year, an argument that initially encountered resistance until it was embraced by Stephen Miller, Mr Trump’s deputy chief of staff.

Plenty of rationales were offered. Venezuela undoubtedly served as a South American beachhead for Iran, Russia and especially China, allowing all three to expand their regional influence at Washington’s expense.

Stepping up military action – first through military strikes on vessels suspected of carrying narcotics and the seizure of shadow fleet oil tankers, and later with the operation that captured Mr Maduro – offered a relatively low-cost way of projecting US power.

But the most important motivations may have been domestic rather than foreign. A core constituency in South Florida, a vital Republican stronghold, has long demanded decisive US action against Mr Maduro, who has propped up the Leftist regime in Cuba, from which many Floridians fled.

A robust Venezuela policy has also allowed Mr Trump to look tough on immigration, homeland security and narcotics smuggling – all key issues for his base.

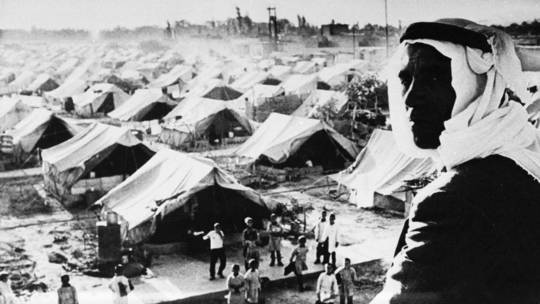

If the Venezuela mission was therefore driven more by domestic than foreign considerations, it will nonetheless have profound consequences across South America, where many fear the return of an era of US military intervention and coup-mongering they hoped had ended with the Cold War.

Friendly and neutral states will feel greater pressure to fall into line. Traditional foes such as Cuba and Nicaragua face a precarious future. If they lose access to subsidised Venezuelan oil, instability may follow.

The potential loss of access to Venezuelan energy will also hurt Russia and China. Russian companies hold significant stakes in Venezuela’s economy through joint ventures in the Orinoco Belt oil fields, while China is the country’s largest creditor.

With Mr Trump clearly eyeing the possibility of the US replacing both countries as Venezuela’s principal energy partner in the post-Maduro era, their ambitions in the Americas have suffered setbacks.

But there are upsides, too.

Resentment in South America and anger across the developing world may yet play into Russia’s hands.

Moscow was quick to denounce “an act of armed aggression” and will be keen to portray the US as a threat to the international order, using the operation to justify its own aggression in Ukraine.

Western moral arguments against Putin’s war will certainly be harder to sustain and will be likely to fall on deafer ears in the so-called “Global South”.

For Beijing, the implications are as consequential. The US has now created a fresh precedent for the use of military force by any major power seeking regime change in its neighbourhood.

Officials in Taipei are therefore likely to have viewed this weekend’s events in South America with particular alarm.

Moscow and Beijing will hope they are glimpsing the contours of a new world order: one defined by regional spheres of influence dominated by regional powers.

In their view, the US is gradually abandoning its role as global policeman and retreating behind the walls of a powerful regional fortress. The multipolar era they have long yearned for may, at last, be dawning.

[Source: Daily Telegraph]

/file/attachments/2988/P1YoungLeaders_622876.jpg)