Inside the mad market for Nazi art

A European dealer has used Truth Social to sell paintings once owned by Hitler’s inner circle, which many feel should be banished forever

It was around August last year that people began commenting on what was being served up between Donald Trump’s rants on his online mouthpiece, Truth Social. Ads kept popping up showing period paintings with headings such as Art of the German Elite, 1933-1945 and German Soil 1933 or American Soil?

The ads clicked through to a page on the website of the German Art Gallery, titled Artworks previously owned by Third Reich leadership. It listed 25 works for sale – most priced between $100,000 and $320,000 – which had once belonged to the likes of Joseph Goebbels, Albert Speer, Hermann Göring and Joachim von Ribbentrop, as well as several that had been in the possession of Hitler himself.

The man behind the gallery – and the ads – is “Marius Martens” (a pseudonym), who works in the financial sector in the Benelux countries. He is in his 60s and has been collecting Third Reich art for about 15 years. He now has the largest private collection in the world: 400 works, including large marble and bronze sculptures and monumental paintings, of which 60 bear the official Nazi Party seal of approval, having been shown at the annual Great German Art Exhibition (Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung, or GDK) between 1937 and 1944.

These works, Martens tells me, are the most sought after and come on to the market at a rate of about one a year. His fascination, he insists, is not ideological – “I’m only interested in art and art history” – and, “from a pure aesthetic point of view”, he genuinely likes the work, which often takes the form of heroic variations on classical ideals and romantic realist “Blood and Soil” scenes extolling rural life (and racial purity).

“I come from 25 generations of Dutch farmers from the northern part of the Netherlands. We don’t like modern art. We like realistic art,” he says – adding, “95 per cent of the public don’t like modern art either”.

On a trip to Berlin, Martens discovered a small room up a back staircase in the German Historical Museum and caught sight of a painting of ploughmen in the fields. When he realised what it was – and that it was hidden away – he thought to himself: “We are not allowed to see that kind of art? What nonsense.” (He notes now that it has many similarities with American New Deal art of the time – hence his Truth Social poser: German soil or American soil?)

On returning home, he bought Peter Adams’s 1992 book Art of the Third Reich, which remains perhaps the most important exploration of the period. It sparked what Martens describes as a “great passion”.

In Martens’s view, only five per cent of the works produced under the Third Reich could be described as “Nazi art”, made for propaganda purposes – “I may have three of those really controversial works, out of 400”. Works featuring Nazi symbols, such as the swastika and the eagle of the party emblem, clearly fit this description, as do busts and portraits of Hitler. In many European countries, it is illegal to display them outside educational or artistic contexts.

Yet “zero per cent” of his clients, Martens claims, buy works for “political or ideological reasons”. They are mostly “very rich entrepreneurs”. “Neo-Nazisdon’t buy this work,” he says. “They don’t have the money, they don’t have the brains.”

That said, he admits he intentionally set out to provoke with the adverts on Truth Social, using the word “elites” in the expectation that it would generate outrage, further sharing on social media and press attention. In that sense, it has worked. But Laura Morowitz, a professor at Wagner College and the author of Art, Exhibition and Erasure in Nazi Vienna, says it was “playing with fire”.

“‘Elites’ is a purposely chosen term,” she adds. “When it’s used, you’re implying that the people at the highest ranks of the Nazi Party were the elite. With the growth of fascism in Europe and the United States, that’s irresponsible.”

Martens was not suggesting they were still the elite, he insists: “No, of course not.” Instead, he identifies as “a rebel”. Art historian Gregory Maertz told The Art Newspaper that he thought Martens “was trolling the Trump administration because there are interesting parallels”.

There are. Trump’s years in and out of power have been dogged by claims that his messaging draws on Nazi-style propaganda, from campaign ads taken down by Facebook in 2020 featuring a red inverted triangle – a symbol used to identify political prisoners in Nazi concentration camps – to idealised blond, blue-collar male workers (“America’s Future”) in the present administration’s Department of Labor ads, and a video posted in January captioned “One Homeland. One People. One Heritage”, thought to echo the Nazi slogan “Ein Volk. Ein Reich. Ein Führer” (“One people. One realm. One leader”).

Martens is keen to steer clear of politics, but notes with surprise the AI-generated image of the US president wearing medieval armour that was posted in November. “I thought, come on people, haven’t you learned anything from the past?” In his view, it had a clear lineage to Hubert Lanzinger’s 1930s painting The Standard Bearer – a portrait of Hitler on horseback in white armour carrying a Nazi flag. “If you’re afraid of reviving Nazis, then study the past,” Martens says.

It was a cost-effective campaign. A US ad agency was offering a competitive deal to advertise across 70 conservative news sites in America. Martens paid $2,800 for a large tranche of posts, then specified that they could appear only on Truth Social. “How on earth was it possible,” he asks, “that for a year I was advertising on there – sometimes between two Trump posts for the whole evening – for $30, the price of two cocktails?”

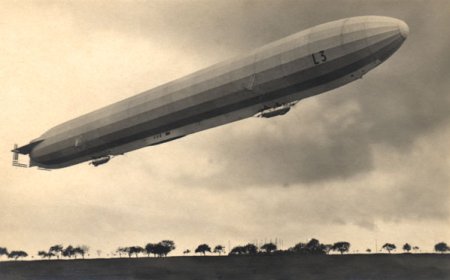

Among the works he advertised as previously owned by the German Führer was naval artist Claus Bergen’s 1937 painting of a U-boat in heavy seas, Wiedererstanden, U-26, which Hitler bought for 4,000 Reichsmark to hang in Speer’s New Reich Chancellery. It is listed for sale at $310,000 – “a bargain”, according to Martens.

“Prices are already 10 times what they were 10 years ago,” he says.

Martens argues that the art of the period has become part of history, invoking the Romans, who were responsible for the systematic annihilation of the people of Carthage in 146 BCE. “Shouldn’t we melt down all these Roman and Greek statues?” he asks. “The past was always terrible.”

Morowitz agrees that “the history of art is not a pretty story for the most part… but when does it become the past and not the present? When you don’t have people who are still immured in that ideology and hoping to revive it. “The Roman Empire is not an active threat any more, and that is not the case for neo-Nazism,” she continues. “When the ideology and the hatred is still alive, then it’s fair to say this is not the historical past, and we have to be careful.”

The German Art Gallery website bears out Martens’s stated interest in art history. It contains detailed biographies of around 150 artists, compiled at a cost of more than €50,000 in acquiring pre-1945 books and exhibition catalogues. No publisher responded when he proposed turning them into a book, he adds, so he put them on his site for free.

They contain many intriguing details. The Bergen painting, for instance, was displayed at the 1937 GDK – probably, it is suggested, as a counterpiece to another Bergen work depicting Germany’s naval bombardment of Almería during the Spanish Civil War, The German Pocket Battleship Admiral von Scheer Bombarding the Spanish Coast. This painting, it transpires, is held by the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, one of seven accused of having been taken as war trophies (the museum did not respond to our request for comment).

Martens is certain it was commissioned in response to Picasso’s Guernica(1937), painted after the Luftwaffe’s bombing of the town in support of Franco’s Nationalists.

“It was commissioned three or four weeks after Picasso showed his work at the Paris World Exhibition. That is not a coincidence. Guernica and Almería were bombed six days apart, with civilians killed in both attacks. It was hung while still wet at the Great German Art Exhibition, after the opening, so it was not in the catalogue. But I found it in the archives in Germany. Hitler notes in his list that he bought it for 8,500 Reichsmark.

“It took me two years and a new curator before [the Maritime Museum] changed the description on their website, which now reflects my suggestion.” Does he think the painting should be returned? “I don’t care that much,” he says. “But it should be in Germany. It is stolen.”

Morowitz is not in favour of hiding Third Reich art away – “you create this kind of forbidden aura around it” – but stresses that it needs to be shown responsibly. She also takes issue with the idea that only five per cent of it is propaganda.

“The majority of works, for example, that were shown at the Great German Art exhibitions each year were not explicitly propagandistic. They were genre scenes. They were landscapes. They were family scenes. But to say that a scene of blonde, braided peasants around a table during the Third Reich doesn’t carry, let’s call it an ideological message rather than a propagandistic one, is a very non-contextual way of seeing it.”

The other major holdings of Third Reich art are in two public collections: the German Historical Museum and the Pinakothek [der Moderne museum in Munich]. “It’s very difficult to get hold of works from the period” because almost of all it – perhaps 98 per cent, Martens believes – has been destroyed since the Potsdam agreement of 1945, in which the Allies set out a framework for the de-Nazification of post-war Germany. “There were fears that Nazism would come back to life. I understand that. But there is hardly anything left.”

Martens says he has bought everything from the GDK exhibitions that has come on to the market in recent years. He once travelled to northern Canada after receiving a letter from a man who wrote: “I understand you are the first one who likes the sculptures of my father…”

It was the son of a prominent Third Reich sculptor whose classical works had appeared at the GDK on several occasions. Martens reached the remote location by seaplane, acquired all eight pieces and had to persuade a local fisherman to ferry the largest – a 75kg bronze sculpture – back to a point from which it could be couriered to Europe.

He does not expect the discovery of any further major pieces, such as the two life-size horses by the Austrian-German sculptor Josef Thorak that once stood outside the New Reich Chancellery and were recovered by German police in 2015.

“There is still a sculpture owned by Hitler in the UK,” Martens says – the life-size marble Sandalenbinder (Sandal Binder) by Fritz Röll, bought at auction in London in 2008.

The major auction houses do not sell Third Reich art, although there are grey areas, Martens notes, such as the work of Carl Paul Jennewein, whose sculptures are displayed in museums in the US and the UK, as well as at the White House. Jennewein was a German-American artist not directly linked to the regime, but he exhibited at the GDK and sold three works to Hitler, Martens says.

Another painting by an artist associated with the regime was hung in 11 Downing Street by Rishi Sunak while Chancellor of the Exchequer: Arthur Kampf’s stirring 1918 portrait of the English seaman Cecil Arthur Tooke as a prisoner of war. Kampf, who was born in 1884, would later create a huge portrait of Hitler against the backdrop of a swastika on a Nazi flag, visible in photographs of Berlin City Hall in 1935.

“The Nazis liked his work, especially his historical work, and he also produced images of Hitler, so he was collaborating,” Martens says. “Does that make him bad? Yes, his morality wasn’t right. Does it make an artwork bad? It’s complex. The thing about Kampf is that he was already a big name in 1910. He didn’t need the Nazis, but he went along with them.”

A DCMS spokesperson declined to comment on the presence of Kampf’s work in the Government Art Collection, but said: “The artwork is not on display in any government department.”

Martens has concluded that eight out of 10 artists of the era were “politically quite neutral”.

“They were young men. Many had been in the trenches of the First World War, which deformed their view of life completely. Then came the Weimar Republic – 10 years of poverty – and then the Nazis arrived and there was a massive amount of money for art. They could build a family, but they were all finished in 1945. It’s a completely lost generation.”

There is also a distinction to be made between the art the Nazis looted from across Europe and the works produced under the Third Reich. Göring, for instance, saw himself as a connoisseur and collector rather than an art thief. Only a tiny fraction of the roughly 1,500 works he hoarded were contemporary Nazi-era pieces; more than half were forcibly transferred – especially from Jewish art collections – or stolen from private and museum collections, three-quarters of them Old Masters. His prized “Vermeer” later turned out to be a forgery.

The looted works Hitler intended for his vast state museum project in Linz included masterpieces by Michelangelo, Rembrandt and Vermeer and, most famously, the Ghent Altarpiece by Hubert and Jan van Eyck.

“They were a bunch of criminals,” Martens says.

The altarpiece, also known as The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, was hidden by the Nazis in the Altaussee salt mine in Bavaria, where it was later discovered by the “Monuments Men”, the group of Allied experts given the task of recovering Europe’s stolen art after the war.

Martens recently came across a work from the same underground cache, discovered by one of the group.

“I bought a painting on eBay last year for $2,000,” he tells me. “It was by Friedrich Stahl. The small gallery that sold it said there was a will on the back, glued there by an American veteran, who wrote: ‘After my death, this painting has to go to the Met.’ Everyone laughed: ‘Who the f--- is Friedrich Stahl?’

“I knew in five minutes. It was a favourite painting of Hitler’s that he bought and designated for the Linz gallery. I’ve never hit the ‘Buy now’ button so hard.”

The painting is now for sale on the gallery’s website for $225,000.

[Source: Daily Telegraph]

/file/attachments/2988/P1YoungLeaders_622876.jpg)