The wheeling and dealing behind South Africa’s AI factories

South Africa is in the grip of an infrastructure supercycle, but it isn’t roads or rails. It is the rise of the AI Factory, windowless fortresses consuming small cities worth of power.

/file/attachments/orphans/AWS_Data_Center_Interior_4_838807.jpg)

Drive past the nondescript, high-security compounds in Isando or Brackenfell, and you wouldn’t guess that inside, the air is freezing, the noise is minimal, and the money is printing faster than a national mint in a debt crisis.

While the average South African factory and ferrochrome smelter is begging Eskom for scraps of power, these data centres have, effectively, privatised their own slice of the national grid.

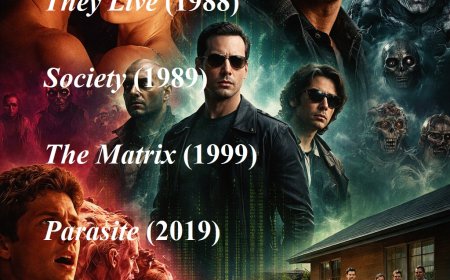

By building 120MW power stations in the Free State and wheeling (the current electricity industry buzzword) that power to cities where they are based, data centres are solving their own load shedding problem by booking up scarce transmission capacity, turning themselves into energy islands.

/file/attachments/2987/Tonydatapic13_InfographicFIXED_973139.jpg)

AWS started the direct investment in renewable energy trend with a 10MW solar plant near Kathu in the Northern Cape in 2021, powering their Cape Town operations. Teraco upped the ante by building a 120MW solar PV facility in Free State, while other companies chose long-term power purchase agreements.

Vantage Data Centers secured 87MW for Waterfall City from SolarAfrica, while Africa Data Centres (ADC) broke ground on a 12MW solar farm near Bloemfontein with Distributed Power Africa to cover the 6MW expansion on its CPT1 site in Cape Town and future Johannesburg sites.

City of Cape Town spokesperson Luthando Tyhalibongo has confirmed the metro supports wheeling arrangements for such “high-energy consumers to offload demand from the local grid.”

But while data centre operators tout solar credentials through these wheeling deals and on-site solar – rooftop solar is not sufficient to meet the demand of these power-hungry, silent factories. Instead, those panels atop the physical buildings are relegated to aircon, electric fence and interior lighting duty.

The immediate backup to keep the chatbots chatting is fossil fuel. And with the rise of AI, the power thirst is becoming unquenchable.

“Data centres are no longer just a technology story – they are an energy story,” NJ Ayuk, of African Energy Chamber fame, was quick to point out in a recent press release framing how these AI factories are reshaping Africa’s energy landscape.

There is even serious talk of nuclear. Dr Yves Guenon, chairman of the French South African Chamber of Commerce and Industry, explained how this burgeoning industry is stretching global nuclear capacity thin.

“International investors are hunting for clean, reliable electrons… Solar plus battery storage simply cannot guarantee for 24/7 AI training clusters.”

In the meantime, to guarantee the 99.999% uptime sold to clients, operators rely on vast fleets of diesel generators.

Cutting environmental corners

There is only one publicly available National Environmental Management Act (Nema) filing that reveals how data centre operators sometimes use Section 24G rectification as a way to legalise expansions made without prior environmental authorisation. ADC made the mistake at their Midrand campus on Old Pretoria Road.

The unfortunate poster child for data centre rules skirting

The original ADC infrastructure dates back to before Nema’s requirements. However, as the facility expanded, adding more diesel generators and fuel storage to keep up with increasing demand and reliability standards, these upgrades triggered environmental listing notices that weren’t authorised at the time.

The situation escalated in 2021 when ADC installed four additional 2.5MW generators, pushing their total backup power capacity over the 10MW threshold. This crossed the line set by Listing Notice 1, Activity 37, requiring environmental authorisation for such activities.

Realising this, ADC submitted a Section 24G application to retroactively legalise their expanded operations. The process comes with an administrative fine (potentially up to R5-million under the Nema amendments) though the exact amount paid is rarely disclosed publicly.

This case highlights a regulatory mismatch with the realities of South Africa’s unstable grid.

Data centres often start with modest backup power and fuel storage, but as load shedding worsens and uptime demands rise, incremental upgrades push them over compliance thresholds.

Many operators only discover their non-compliance after the fact, prompting Section 24G applications to regularise their operations and avoid delays to critical infrastructure.

Tyhalibongo confirms that the high volumes of diesel required for backup power trigger mandatory Environmental Authorisations from the National Department of Environmental Affairs, before any storage.

Skipping this step to rush a facility online is a gamble operators may be willing to take, choosing to pay the fine later rather than delay the “go-live” date.

[Source: Daily Maverick]