Why the real target of Trump’s campaign in Venezuela is Cuba

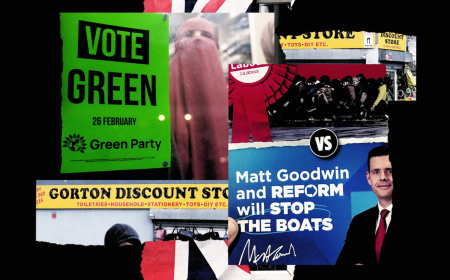

The US president is amassing firepower in the Caribbean to force Maduro out, but the ultimate goal may be regime change in Havana

When the attorney general of the United States took personal charge of Operation Mongoose, he declared it America’s “top priority”, saying “no time, money, effort or manpower” was to be spared.

The official in question was Robert Kennedy and the supreme objective that mattered more than anything else was toppling Fidel Castro and “liberating” Cuba from Communist rule.

Operation Mongoose and its famously futile campaign of subversion began in November 1961, inspiring plenty of Hollywood movies but not the dawn of freedom in Cuba.

Now, incredible though it seems, the evidence increasingly suggests that history may be repeating itself and Donald Trump’s administration is considering a comparable enterprise.

Trump has already concentrated about 10 per cent of the entire US Navy in the Caribbean, including guided missile destroyers, a nuclear-powered attack submarine and two amphibious assault ships. This formidable force has just been strengthened by the arrival of the USS Gerald R Ford, the world’s biggest aircraft carrier, having steamed westwards across the Atlantic at the head of a naval strike group.

The primary target of this military build-up – America’s biggest deployment in the Caribbean since an intervention in Panama in 1989 – is Venezuela’s far-Left and bitterly anti-US regime under Nicolas Maduro, the authoritarian successor to the late Hugo Chavez.

But that is not the whole story. Experts believe that Trump, and especially Marco Rubio, the US secretary of state, may see regime change in Caracas as a necessary prelude for what they want most of all, which is regime change in Havana and the final “liberation” of Cuba, exactly 65 years after President Kennedy made this America’s top priority.

The rulers of both countries are certainly seen by Washington as ruinous, repressive, corrupt and dangerously close to America’s adversaries, particularly China and Russia. And the tradition of America asserting its pre-eminence over its own hemisphere – symbolised by Trump’s unilateral decision to re-label the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America – goes back more than two centuries to the Monroe Doctrine of 1823.

The stubborn survival of Cuba’s regime, meanwhile, is the ultimate example of unfinished business, as the secretary of state has sometimes hinted.

“The US will continue to stand for the human rights and fundamental freedoms of the people of Cuba”, said Rubio on July 11, “and make clear no illegitimate, dictatorial regimes are welcome in our hemisphere.”

Soon afterwards, on August 7, America escalated the pressure on Venezuela by doubling the sum offered for “information leading to the arrest and/or conviction” of Maduro to $50m (£38m) – twice the amount advertised for Osama bin Laden.

The US State Department publicly accused Maduro of being the leader of the Cartel de los Soles (the “Cartel of the Suns”), described as a narco-terrorist group “responsible for trafficking drugs into the United States”.

In September, Trump turned up the heat yet further with a new policy of sinking without warning any vessels suspected of carrying drugs to the US. Speedboats leaving Venezuela were soon being incinerated in international waters, with Trump himself gleefully tweeting footage of one strike on September 2 that resulted in “11 terrorists killed in action”. So far, 22 boats have been destroyed by missiles, killing 83 people.

But America’s military build-up goes far beyond amassing the firepower needed to sink speedboats. So what exactly is the president’s objective? Christopher Sabatini, the senior research fellow for Latin America at Chatham House, in London, says that Trump is probably not contemplating a “reckless beyond belief” full-scale invasion of Venezuela.

The country is more than three times the size of Britain and has a population of 28 million, requiring hundreds of thousands of troops for any occupation. Instead, Sabatini believes that Trump’s aim is to threaten air and missile strikes – and perhaps launch them – in order to trigger Maduro’s downfall.

“Trump wants to scare the military leadership around Maduro into getting rid of him,” says Sabatini. “The goal is to rattle the military into staging a palace coup.”

As for who would rule a post-Maduro Venezuela, Trump may have an answer. Last year, Edmundo González, an opposition leader, won Venezuela’s presidential election, only for Maduro to announce a fraudulent victory for himself and force his opponent into exile in Spain.

Another opposition leader, María Corina Machado, was banned from standing in that contest; she is now hiding somewhere in Venezuela. Last month, she won the Nobel Peace Prize for what the committee called her “tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela and for her struggle to achieve a just and peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy”.

Either González or Machado would be legitimate inheritors of power. But the most likely outcome of any Trumpian intervention would be a general succeeding Maduro. Someone who had just taken the immense risk of mounting a military coup, even one backed by US air strikes, would perhaps have little reason to decide on their first day in Miraflores Palace – Venezuela’s White House – to hand over power to Machado or González.

Yet suppose America were, somehow, to succeed in engineering Maduro’s downfall. What might be the consequences? This question raises the most intriguing possibility of all.

The end of the Cold War and the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991 were also supposed to bring about the political demise of Fidel Castro in Cuba. Having predictably wrecked his country’s economy with Communist policies, Castro was dependent on Soviet subsidies.

One reason why he survived their sudden withdrawal was that Venezuela under Hugo Chavez stepped into the breach and began supplying Cuba with 100,000 barrels of cheap oil every day, a fraction of the bountiful reserves in the Orinoco Delta – which remain the largest in the world. At a crucial moment, Venezuela threw Cuba what Sabatini calls a “lifeline”.

And one person who took that personally was a young Cuban-American called Marco Rubio, then a mere “city commissioner” (or councillor) in Miami, who was destined to become the Republican senator for Florida and, now, US secretary of state and national security adviser.

Rubio is the first Cuban-American ever to hold the two latter positions. Having spent a lifetime steeped in the visceral anti-Communism of south Florida, the home of exiles from Cuba and Venezuela, he suddenly has a chance to rid the western hemisphere of both regimes.

Venezuela without Maduro would no longer be Cuba’s lifeline. And without that lifeline, Cuba’s own regime would be vulnerable.

Fidel Castro died in 2016 after handing over power to his brother, Raúl, in the unashamedly dynastic fashion of a true socialist republic. Raúl then retired as first secretary of the Cuban Communist party when he turned 90 in 2021.

Cuba is now ruled by president Miguel Díaz-Canel, the first non-Castro to be in charge of the island since the revolution of 1959. This 66-year-old engineer would be in the crosshairs of any American regime change operation that begins in Caracas and continues to Havana.

There is little doubt that Rubio, at least, has exactly that in mind. “He’s been a politician in the anti-Communist hothouse of south Florida,” says Sabatini. “For him, this is a very personal project. He’s in regular touch with the Venezuelan opposition – and Cuba is the next step.”

This goes back to Rubio’s earliest years in the Senate and his dogged opposition to Barack Obama’s attempt to normalise ties with Havana in 2014. “Rubio’s legacy project is regime change in Cuba,” a Senate staffer toldForeign Policy magazine earlier this month. “This is Rubio’s chance to do what he has always wanted to do.”

One of Trump’s first acts, within 24 hours of regaining the White House, was to overrule the decision of his predecessor Joe Biden, and ensure that Cuba stayed on the US list of state sponsors of terrorism.

Cuba’s leaders are grimly aware that the US administration, and particularly Rubio, are now gunning for them. “The current secretary of state was not born in Cuba, has never been to Cuba, and knows nothing about Cuba,” said Bruno Rodríguez Parrilla, Cuba’s foreign minister, in an interview with Associated Press. “There is a very personal and corrupt agenda that he is carrying out, which seems to be sacrificing the national interests of the US in order to advance this very extremist approach.”

But there are good reasons to question whether the downfall of Maduro would shake the foundations of Havana’s regime. Under his calamitous rule, Venezuela’s oil production has been cut in half, leaving steadily less available for Cuba. By last year, Venezuela was giving its ally only 32,000 barrels per day, down two-thirds from the peak amount.

Cuba would probably be able to cope with the loss of that relatively modest supply. Given that oil prices are low, Havana might be able to buy what it needs from another exporter. Vladimir Putin could be tempted to fill the gap, particularly as Russia is permanently hunting for buyers for its sanctioned oil which must be sold at a discount.

Cuba’s regime has now outlived its founder, Fidel Castro, by nearly 10 years. For most of the last six decades, America has systematically underestimated its resilience. The question is whether justified revulsion for Havana’s corrupt autocracy leads to sensible and measured policy. Neither the invasion of Cuba by CIA-backed exiles at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961 nor the covert efforts of Operation Mongoose are encouraging precedents.

Whether Trump feels the same way as Rubio is also open to question. A president who rose to power by scorning foreign adventures seems hardly likely to launch a grand scheme to overthrow two regimes and remake the western hemisphere by force of arms.

But could there be any greater temptation for Trump than to succeed where his predecessors, going as far back as Kennedy, so demonstrably failed? And if there is any part of the world where Trump and his Republican supporters might be willing to intervene, it is surely in their own region.

Latin America is the foremost source of drugs, crime and illegal migrants heading for the US. Trump might present the project of dealing with two hostile states, one of which is only 90 miles off the Florida coast, as the ultimate example of protecting the homeland by cleaning up the neighbourhood. The weeks ahead will be decisive.

[Source: Daily Telegraph]