‘There’s this whole other story’: inside the fight to end slavery in the Americas

The Great Resistance, an expansive new book by author and historian Carrie Gibson, brings together often unheard narratives to tell the bigger picture of a difficult time

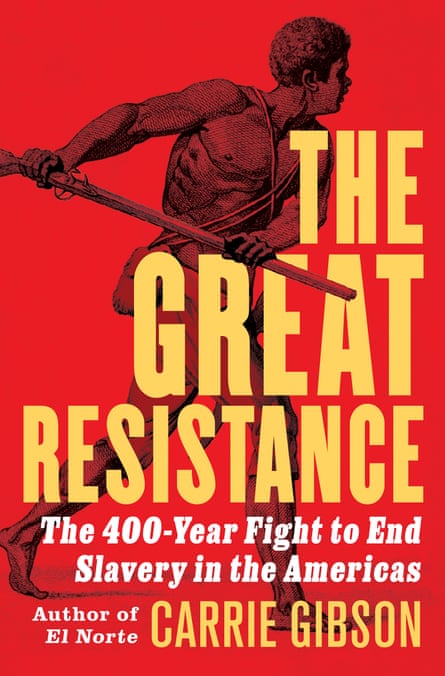

The Great Resistance is Carrie Gibson’s third book, and her third about the history of the Americas, plural. It follows Empire’s Crossroads: A History of the Caribbean from Columbus to the Present Day, from 2014, and El Norte: The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic North America, published five years later. The subtitle to the new book indicates its roots in the first two: The 400-Year Fight to End Slavery in the Americas.

“I was led by both my own curiosity and also a frustration,” Gibson said, of how she came to retell that four-century fight over 500 absorbing pages.

“So much that is known about the rise of slavery, the system of slavery, and the end of slavery, tends to be in the English-speaking world. So the English-speaking historiography looks at the US, it looks at Jamaica, but there’s this whole other story.

“I’ve spent a lot of time in Cuba, so I write about the Spanish-speaking world and the Spanish empire, and then there’s slavery in Brazil, which is a whole other thing. And when you’re in the scholarship, it’s linguistically divided. I wanted to bring it all together. I wanted to see what it looked like.”

Gibson is herself well-traveled: from the American south, she moved to London, wrote and edited for the Guardian, then went to Cambridge for a PhD centered on the Haitian revolution of the late 18th century, an epochal event in the fight for freedom. Now based in South Korea, she refuses to stick to well-trodden paths.

“There’s been a big historical turn,” Gibson said. “In the last 20 or 30 years there’s become a lot more interest in the movement by enslaved people to get their own freedom, versus white abolitionism, which for a long time, certainly in Britain, received a lot of attention.”

The Great Resistance recounts such attempts for freedom. Most involve desperate violence. The book begins in nightmare.

“The road to freedom is lined with bodies,” Gibson writes. “Some lie in the darkest recesses of the sea, like the ‘hundred Men Slaves [who] jump’d over board’ from the Prince of Orange during a balmy evening in March 1737 … ‘resolv’d to die’,” at least 33 succeeding, “sunk directly down”.

It happened in the Caribbean not far off Saint Kitts, then contested by Britain and France. The 360 enslaved people aboard, bound for Virginia, were from Bonny in what is now Nigeria.

“It’s definitely a dark book,” Gibson said. “But I didn’t want to dwell too much on the violence inflicted on enslaved people, because I feel like there’s a lot of that in other books, and there’s also a critique about white voyeurism, of violence to Black bodies.

“If you read books about plantation history, or the rise of slavery, it is a horrible, violent story. But so is the story of freedom. What I tried to do is focus on the actions and reactions of enslaved people trying to get to freedom. So jumping off a ship – that’s their choice. Or a conspiracy, a revolt that is violently suppressed, I show that within the context of what they’re trying to do, rather than the arbitrary and horrific violence meted out by the system.”

Gibson considers the history of transatlantic slave trade but does not focus on it. She points out that her endnotes “can point people to more detailed books about the horror of the Middle Passage”, terrible voyages that took enslaved people from Africa. When the Prince of Orange plied the route, she notes, the ship’s captain did not record the names of those he transported or who jumped to their deaths.

That “really stuck with” Gibson, because in “contemporary accounts of resistance they might name the ringleader or a few others, and then it’s just numbers: it’s just, ‘16 slaves hung’, often.

“Sometimes they do put names so that they can compensate the enslavers, but I was always really struck because in academic practice now, there is a lot of discussion about archival silences. And I felt in this story the silences were really, really loud. Here are these people rebelling against the system and nobody knows their names. Nobody can be bothered to record their names. They don’t even know what their names are. They don’t even know what names they’ve been given.”

Some names are known well. Nanny, the woman who led escaped enslaved people (“Maroons”) in Jamaica and forced a treaty with the British, in 1740. Denmark Vesey, who rebelled in South Carolina in 1822. Nat Turner, who fought back in Virginia in 1831. Black campaigners are present too: US giants such as Frederick Douglass, lesser-known names like Robert Wedderburn and Olaudah Equiano, campaigners in Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Prominent figures outside the Anglosphere include Lourenço da Silva Mendonça, “a member of the royal family in Pungo-Andongo, a part of what was then the kingdom of Kongo”, who in the 1680s, under his European name, became “one of the earliest abolitionists from Africa”. Forced to Brazil, Mendonça returned to Europe to fight for freedom, ultimately making his case at the Vatican in Rome, “anticipat[ing] the contemporary struggle for human rights”.

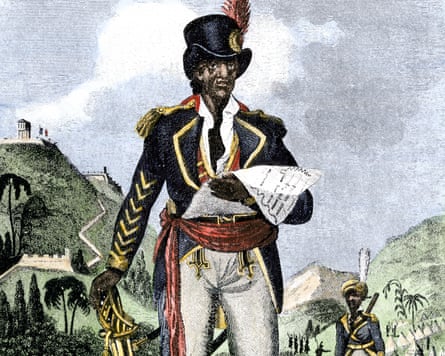

Among violent struggles, there is of course Haiti and its successful revolution against French rule, led by Toussaint Louverture, a great figure of Black history. Born enslaved, as a free man Louverture “purchased at least one slave and, while leasing his son-in-law’s coffee plantation, oversaw 13 others”. As Gibson notes, the fight against slavery was never clean, “noble sentiments” often “giving way to economic realities”.

Lesser-known cases include that of Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua, taken from modern-day Benin to Brazil in the 1840s, treated brutally, then taken to Rio and “almost bought by a ‘colored man’”. In a narrative of his life published in New York in 1854, after his escape, Baquaqua said he recounted that near-sale to “illustrate that slaveholding is generated in power, and anyone having the means of buying his fellow creature with the paltry dross, can become a slave owner, no matter his color, his creed or country.”

Gibson found Baquaqua “in the course of researching this book. He’s not well known, like Frederick Douglass, like Nat Turner … We don’t have any records of his life. We don’t know what this guy was doing.” Like many of her subjects, he proved “very hard to track”.

Well aware that readers “want simple narratives”, Gibson said the challenge of explaining horrendously complicated realities was something “really frustrating about being a historian right now. Publishing is grappling with nonfiction losing ground to ‘romantasy’ and escapism and stuff. If you want this book to be a really happy story, it isn’t. I didn’t even get into the afterlife of slavery. Just because the practice and the institution ends [with abolition in Brazil, in 1888] we’re living with the afterlives and that’s completely unresolved.”

In the US, Gibson argues, one such lasting effect of slavery is found in societal violence.

“You needed a culture of violence to suppress slave revolts, to make people work, to stop runaways. I think there’s a legacy that has not been grappled with. Why do you think there are guns in America? Who do you think they were used for? Initially, it wasn’t to kill bears out west. It was to suppress, it was to keep order in the east. First, it was to kill Native Americans, obviously. Then the need for guns to keep away the Brits [founding myth of US gun-rights lobby] was the least of the concerns.

“One thing I learned in doing this book is that the Citadelin South Carolina [a leading military college] was the result of the fear around the Denmark Vesey revolt. There’s a statue to Denmark Vesey in this park in Charleston that is not very far from the Citadel. The founding of the Citadel was about, ‘Oh, we can never let this kind of conspiracy happen again.’”

Another lasting factor in the history of slavery, in the Caribbean and South America in particular, is sugar: cultivated by Europeans using forced African and Indigenous labor every bit as brutally treated as were enslaved people in the cotton fields of the US south.

To Gibson, sugar was “the cocaine of its day. No one needs sugar. Cotton, well, it’s a staple. You make clothes from it. But nobody needed sugar. Arguably, nobody really needed the main commodities of the Caribbean: sugar, coffee, chocolate, cacao, in some of the islands, and Mexico and South America, indigo. Indigo had industrial or dying uses, but if you look at the commodities, most are absolutely luxuries.

“And this intersects with scholarship and increased awareness about commodities through history, and luxury goods, the rise of the consumer society. Sugar’s just poisonous, really, and we’re all addicted to it, and the world is getting obese because of it, and that’s what I find so extraordinary: all these people suffered so much for something no one needed. To me, if there’s a starting point of the modern world, that’s it.”

[Source: The Guardian]