Generation AI: fears of ‘social divide’ unless all children learn computing skills

Children are growing up as AI natives and experts say computing skills should be on par with reading and writing

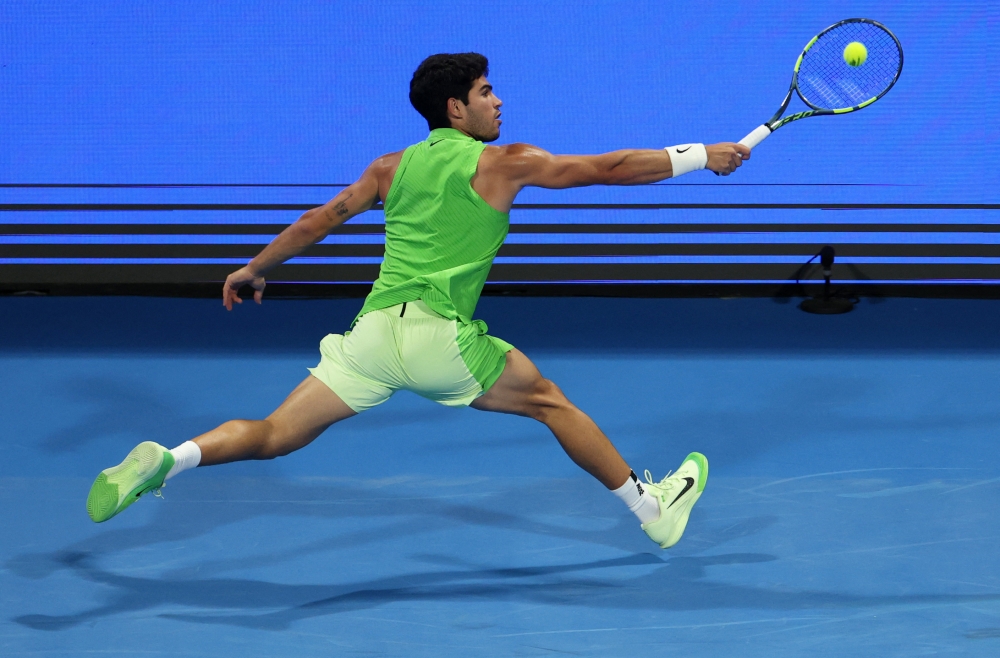

In a Cambridge classroom, Joseph, 10, trained his AI model to discern between drawings of apples and drawings of smiles.

“AI gets lots of things wrong,” he said, as it mistakenly identified a fruit as a face. He set about retraining it and, in a flash, he had it back on track – instinctively understanding the inner nature of artificial intelligence and machine learning in a way few adults do.

His friends from the St Paul’s C of E primary school coding club tapped away to build their own AIs with similar dexterity. Just as people born in the early 20th century never knew a world without manned flight, and generation Z has always lived with social media, Joseph and his friends are AI natives.

Here, on one December morning, some of them were being taught the principles and practicalities of the potentially world-changing technology that experts fear may pass large numbers of people by and leave them disempowered.

Philip Colligan, the chief executive of the digital education charity the Raspberry Pi Foundation, has warned of a “big split” in society between people who grasp how AIs work and are able to control them – challenging their increasing role in automating decisions in areas including housing, welfare, health, criminal justice and finance. On the other hand, there could be a cadre of AI illiterates who risk social disempowerment.

Colligan, a leading expert in technology and its social impacts, told the Guardian AI literacy must become a universal part of education on a par with reading and writing to avoid a social divide opening up.

“There is a world where you’ve got a big split between kids who understand, have that core knowledge and therefore are able to assert themselves and those who don’t,” said Colligan, whose charity is affiliated to the £600m British low-cost tech hardware startup of the same name. “And that could be really very dangerous.”

His warning was backed by Simon Peyton Jones, a computer researcher who led the creation of the schools national curriculum for computing in 2014, prior to the AI boom. He called for a new digital literacy qualification for all schoolchildren that would ensure they know how to use AIs in a critical way.

“If it’s simply a black box, then [its actions] seem like magic,” he said. “If you know nothing about how the magic is working that is terribly disabling. I am very worried about students leaving school without having agency in the world.”

Their comments came amid a fall in the number of children studying computing, with 2025 entries for a GCSE in the subject down across the UK. Today, three times more people take history and nearly double the number take biology, chemistry and physics. At the same time, use of AI systems nationwide has been surging – up 78% in the year to September, according to polling by Ipsos.

Part of the belief that learning computing skills is becoming redundant comes from some of the big AI companies, which argue their systems are going to automate coding. Anthropic’s chief executive, Dario Amodei, said in October that 90% of its own coding was automated using its Claude AI model. Meanwhile, 2025 was the year when “vibe coding” became a common phrase – capturing the idea that AIs would allow humans to build software by using natural language instructions rather than specialised code.

Political leaders such as Keir Starmer have also suggested coding is becoming redundant. As leader of the opposition in 2023, he said: “The old way – learning out-of-date IT, on 20-year-old computers – doesn’t work. But neither does the new fashion, that every kid should be a coder, when artificial intelligence will blow that future away.” It has created the idea that understanding the inner workings of a computer may be less relevant in the future.

“I think they’re just overhyping the benefits,” said Colligan, whose charity works in schools across dozens of countries.

“This message is leaking out that the kids don’t need to learn this stuff any more and that is not only flawed it is dangerous. We’re already talking to teachers in lots and lots of schools around the world, not just the UK, saying: ‘We can drop computer science now, right?’ That’s a problem.”

He added: “All of us are going into a world where more and more of the decisions we encounter every day will be taken by automated systems. At the moment it’s what movie should I watch next or what song should I listen to? Fairly soon it’s going to be finance decisions, healthcare decisions, criminal justice decisions. If you don’t understand how those decisions are being made by automated systems, you can’t advocate for your rights. You can’t challenge them, you can’t critically evaluate what’s being presented to you.”

In December, the former deputy prime minister Nick Clegg, who is now an AI investor, predicted that “we will move from staring at the internet, to living in the internet”.

Colligan said: “My concern is there will be a gap between kids based on their socioeconomic background. Some kids who go to great schools, who are able to teach this stuff, will be in a much stronger position as citizens, whether or not they’re using technology for their job. Those kids who are in communities where they don’t have access to [AI literacy teaching] will be passively on the end of a whole load of automated decisions.”

In the coding club, the seven- to 10-year-olds are taught how AIs work. The lessons were clearly having an effect on Joseph. He said he thought AI “will probably be good, but if lots of people believe it when it’s wrong it will have a bad impact on them”.

He was not interested in letting the AI do the coding of the video games he planned to make. “It might do it differently to what you want,” he said. “It might also do it wrong and you need to know how to solve it … I’d like to be in charge of the AI. If the AI is in charge of us, we wouldn’t really be able to control what we’re doing and that would be bad.”

[Source: The Guardian]