Why exiled crown prince may not be the answer to Iran’s problems

Reza Pahlavi is courting Donald Trump after 50 years abroad but some Iranians see him as pampered, inexperienced and uncharismatic

His name has echoed through the blood-soaked streets of Iran’s cities. “Pahlavi is returning,” some protesters have cried defiantly. “Long live the Shah!”

Amen, has been the response from parts of Washington, where there is no shortage of figures who see Reza Pahlavi as a saviour-in-waiting – a man destined to deliver Iran from the suffocation and extremism of the Islamic regime that overthrew his father in 1979.

Yet amid the growing enthusiasm for the exiled crown prince, who has emerged as an unexpected figurehead of the protest movement, a chorus of seasoned voices is urging Donald Trump not to risk repeating the mistakes of the past.

Mr Pahlavi could, they fear, prove to be another Ahmed Chalabi – an exiled pretender lionised in Washington as the man to redeem a Middle Eastern state, only to be rejected at home.

In the decade before the American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, Chalabi ingratiated himself with neoconservative heavyweights, persuading Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle that he was the ideal successor to Saddam Hussein.

Though the Americans gave Chalabi – who died in 2015 – a senior role in Iraq’s transitional government, it soon became clear that most Iraqis could not stand the man.

When voters were finally given their say in 2005, his party scraped just 0.5 per cent of the vote.

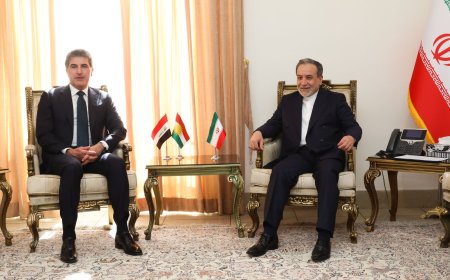

Mr Pahlavi, 65, the heir to Iran’s Peacock Throne, shares some traits with Chalabi: affability, polish, and a gift for cultivating powerful allies abroad.

Over the weekend, according to Axios, he held secret talks with Steve Witkoff, Mr Trump’s golfing buddy and envoy for everything.

He has also won enthusiastic backing from senior figures in Israel, holding a high-profile meeting with Benjamin Netanyahu, its prime minister, in 2023.

But, as with Chalabi, it remains unclear how popular Mr Pahlavi is in his own country.

Some analysts warn that attempting to foist him, even as a transitional leader, on the Iranian people could unleash bloodshed, civil war or even the fragmentation of Iran.

“The Chalabi example is important,” says Renad Mansour of Chatham House, the international-affairs think tank.

“What we’ve learned from Iraq, and from many other contexts, is that someone returning after decades in exile does not have a local constituency. The idea that such a figure can simply come back and claim a popular mandate is a recipe for failure.”

Those warnings appear to have reached the White House. Mr Trump has struck a more circumspect tone than some of his advisers in recent days and has so far resisted calls to meet Mr Pahlavi in person.

“He seems very nice,” Mr Trump told Reuters on Wednesday. “But I don’t know how he’d play within his own country. I don’t know whether or not his country would accept his leadership.”

Whether growing numbers of Iranians genuinely see Mr Pahlavi as a saviour is difficult to judge.

During earlier waves of unrest, his perceived aloofness and lack of sustained engagement dented his standing.

During the aborted uprising of 2019, while supporters were declaring loyalty to him under fire, he was photographed on a scuba-diving holiday in the Caribbean.

Since then, lessons appear to have been learned. In the absence of any other effective opposition leader – most potential rivals languish in prison – Mr Pahlavi has increasingly been a rallying symbol for an otherwise fragmented protest movement.

Optimists say that Mr Pahlavi could be a figure from Iran’s past capable of delivering its people from a horrific present and guiding them to a freer, more hopeful future.

There is no doubt that genuine affection for both Mr Pahlavi and the monarchy exists in parts of the country, particularly in western and southern provinces that historically backed the Pahlavi dynasty.

Elsewhere, however, support may be thinner, rooted more in nostalgia or desperation than conviction.

Pro-monarchy slogans often express rejection of the regime rather than a clear hankering for restoration of the throne or for Mr Pahlavi himself to lead, some analysts say.

“Because the Islamic Republic is by definition anti-monarchist, chanting ‘Long Live the Shah’ is often about provocation,” says Maziyar Ghiabi, director of Persian and Iranian studies at the University of Exeter. “The Shah is being used as a symbol of dissent.”

Opposition to Mr Pahlavi is also real. Many Iranians remember the late Shah’s rule and the brutality of the Savak, his feared secret police.

Others see his son as pampered, uncharismatic and too inexperienced to rule a vast, complex and battered country that he has not set foot in for nearly five decades.

Among certain minorities – particularly Kurds, Azeris and Balochis – antipathy towards the Pahlavi name runs deep. In some protest-hit regions, chants have reflected this unease: “Death to the oppressor, be it king or supreme leader.”

That such divisions are already visible within the protest movement only heightens the need for caution.

“If the regime falls and someone like Reza Pahlavi comes to power, that is the easiest route to internal conflict,” says Prof Ghiabi.

“Various segments of Iranian society – starting with ethnic minorities – would be dissatisfied. It is the surest way to destabilise the country, and could lead to civil war and separatism.”

[Source: Daily Telegraph]