Thousands of former regime remnants in SDF ranks

Military bloc or bargaining chip?

Amid Syria’s constantly shifting landscape, shaped by fragile international and regional balances, a notable strategic shift is emerging in northeastern Syria, raising questions about the region’s near and long-term future.

This shift concerns the integration into the ranks of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) of large numbers of people whom the Syrian government describes as “remnants of the defunct Syrian regime,” according to information obtained by Enab Baladi from four sources, one of them a government employee working in the Syrian intelligence services, two working within the SDF, and a journalist at one of the SDF affiliated media outlets, in addition to eyewitnesses from the area.

According to the information obtained by Enab Baladi, at least more than 4,500 former regime personnel have joined the SDF, deployed across several locations in the cities of Raqqa (in northeastern Syria) and al-Hasakah (in northeastern Syria).

In this investigation, Enab Baladi reviews the most prominent information gathered from these sources and interviews researchers, experts, and people familiar with the issue, to examine the reasons why former regime personnel are joining the SDF and what the SDF seeks to gain from bringing them into its ranks.

In the oil fields

A member of the Kurdish staff working at the al-Omar oil field (in Deir Ezzor province, eastern Syria) told Enab Baladi that more than 2,200 officers, noncommissioned officers, and rank and file members joined the field as a first batch in July.

The integration of these personnel began after the fall of the regime, and their number has now reached more than 4,500 across northeastern Syria. Their main centers are the Koniko gas field and the al-Omar oil field, and they have come from former regime military formations in the Syrian Desert (in central and eastern Syria) and other areas, such as the 17th Division in Raqqa and the Kawkab Regiment in al-Hasakah, according to a source within the SDF.

This military integration is not only a shift in individual loyalties, it is a repositioning of an experienced combat bloc now deployed at highly strategic sites, most prominently the al-Omar oil field, following the withdrawal of US forces from its surroundings.

The new military bloc, deployment, and backgrounds

The prominent figures who have joined have sensitive and high-level military backgrounds within the former regime’s structure, revealing what sources describe as an SDF attempt to attract “command level expertise,” such as:

- Brigadier General Ali Khaddour, a former officer in the 4th Division, which used to be commanded by Maher al-Assad, brother of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, and one of the most powerful and most brutal military and security formations in the former regime.

- Colonel Munhil Khaddour.

- Major Samer Deeb, from the 17th Division.

- A collective defection from the 47th Regiment, involving more than 100 members of the regiment that had been stationed on Jabal Kawkab in al-Hasakah (in northeastern Syria).

- Brigadier General Shadi Dayoub, formerly with the Republican Guard, from the city of Latakia (on Syria’s coast), who took part in several battles in Deir Ezzor during the period when the Free Syrian Army was in control, and later in battles against the Islamic State group.

With the launch of the “Deterring Aggression” campaign and the SDF’s entry into Deir Ezzor city, Dayoub moved into SDF-controlled areas before the arrival of Military Operations Administration forces, after he was accused of committing war crimes against residents of Deir Ezzor.

- Ghassan Tarraf, an officer with the rank of brigadier general.

- Rani Hikmat Hassoun, a warrant officer from the Republican Guard, originating from Latakia.

- Dhirar al Abdullah, a sergeant from Deir Ezzor and one of Shadi Dayoub’s close associates, who now resides in the al-Omar oil field.

- The two brothers, “Dhu al-Himma” and Haidar Moussa, and both from the Republican Guard.

- Several colonels from the 3rd Division, which used to be stationed in the al-Qutayfah area in the countryside of Damascus (southern Syria).

According to information obtained by Enab Baladi, they are accused of storming and shelling several areas across Syria, which forced them to flee and seek refuge with the SDF to escape accountability.

A member of the Revolutionary Youth (Jwanen Shorashkar) organization, which operates in SDF areas, told Enab Baladi that there are camps dedicated to training these “regime remnants.” The number of those who have arrived from areas along Syria’s coast to the al-Malabiya Regiment in al-Hasakah and the Kawkab Regiment in Raqqa has reached more than 1,500 officers and rank, and file members.

According to information from sources inside the SDF, former regime personnel entered northeastern Syria through the Semalka border crossing with Iraq’s Kurdistan Region (in northeastern Syria).

Inside the al-Omar field, former regime personnel coming from the coastal cities are deployed in two groups. The first group took up positions, after the coalition’s withdrawal from the US base, in their former deployment points as SDF special forces (commandos).

The second group is based at the headquarters of the YAT force, which is considered one of the SDF’s core elite units, relied on for storming operations and airborne raids, and trained by US Special Forces, according to a member of Jwanen Shorashkar.

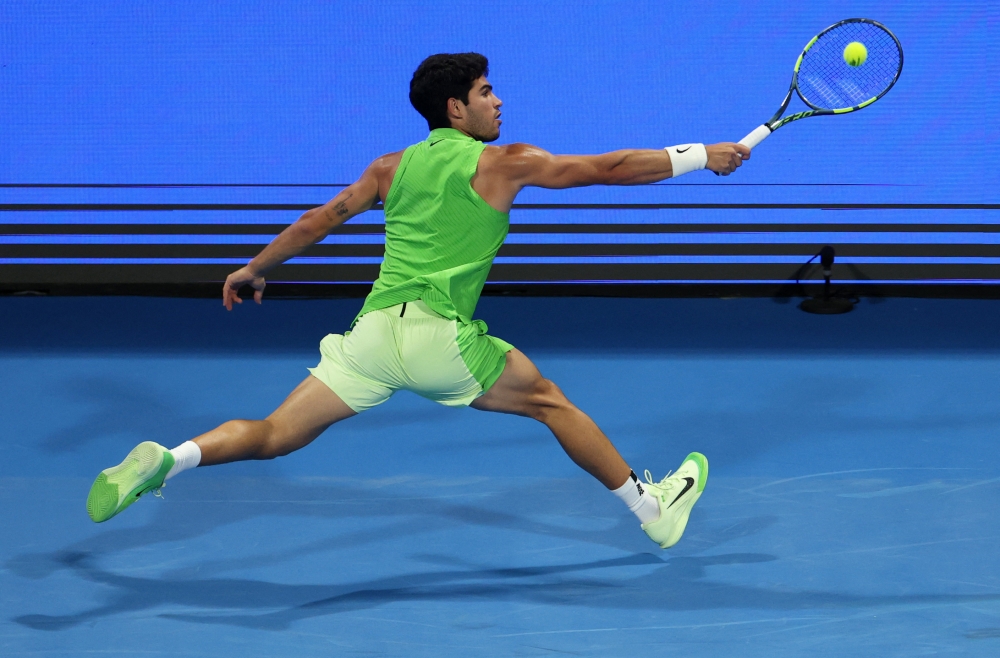

Syrian Democratic Forces fighters during the graduation of a batch of special forces, 13 August 2025 (SDF/Media Center)

Backstage understandings

A journalist working for an SDF-affiliated outlet said that there are helicopters at Qamishli Airport (in al-Hasakah province, northeastern Syria), believed to be Russian, carrying out intermittent flights almost daily.

At the beginning of last October, several former regime officers were transferred to Qamishli from Syria’s coastal region.

Ibrahim al-Hussein, a journalist from Deir Ezzor and director of the al-Sharqiya Post website, confirmed to Enab Baladi that there is indirect coordination between the SDF and former regime personnel, which he considers to serve broader security and political goals.

According to al-Hussein, these “remnants of the regime” are joining to preserve their influence and secure a place for themselves in any future settlement relating to areas east of the Euphrates River, which he describes as “Syria’s treasury” because of its oil resources.

He pointed out that there is a track under discussion on how to integrate the SDF into the new Syrian army, and that this track includes a clause obliging Damascus to accept the deployment of SDF forces across all Syrian territory.

The integration of former regime officers, he argues, facilitates this process, removes operational barriers, and paves the way for relying on local forces within the framework of “security decentralization”, according to the director of the al-Sharqiya Post website.

Al-Hussein added that the major powers, Russia and the United States, are not far from this coordination, and may even be facilitating it.

In his view, Russia strongly encourages this convergence to ensure the stability of oil and gas areas and sees it as a necessary step in the process of gradually reintegrating SDF-controlled areas into the Syrian state, in preparation for a future US withdrawal.

The United States, he believes, remains cautious, but turns a blind eye as long as this coordination serves its primary objective of fighting the Islamic State group and maintaining the relative stability that protects its interests in the region.

He considered that the most dangerous challenge facing the SDF today is the erosion of its credibility, both internally and externally, due to rising corruption, especially after the inclusion of former regime personnel, raising serious fears that the SDF is turning into a “refined version” of the regime Syrians once rose up against.

Salaries and disparities

According to a Syrian journalist who works for an SDF-affiliated media outlet, one of the main reasons former regime personnel are heading to northeastern Syria is the high salaries, which can reach 1,000 US dollars.

The economic factor is the strongest driver behind this shift. Joining the SDF has become a lifeline for these officers in the face of economic collapse in regime held areas following the fall of the government.

During the severe economic decline Syria experienced before the regime fell, salaries for soldiers in the now dissolved army did not exceed a few tens of dollars.

By contrast, the SDF offers generous salaries to the new arrivals, up to 350 dollars for an ordinary fighter and 500 dollars for a noncommissioned officer, while officers are paid according to their military rank, with some earning as much as 1,000 dollars.

According to Enab Baladi’s monitoring, more than 50 SDF members have defected since the beginning of last October because of what they describe as the “deep rift” the SDF has created within its ranks and the way it treats former regime officers who have joined its forces.

Their defection came in protest at major salary discrimination, as the newcomers start at 350 dollars, while long-serving SDF members who have fought for years earn no more than 150 dollars at most, something that has triggered serious internal resentment.

Extortion at checkpoints

With the entry of former regime personnel into SDF ranks, theft and extortion at checkpoints have become widespread, to the point of becoming impossible to deny.

An employee at a civil society organization was stopped about two months ago at the al-Sinnur checkpoint in eastern rural Deir Ezzor, where 6,000 dollars and other possessions were confiscated. It was not an isolated incident, but part of a recurring pattern that suggests systemic corruption at some checkpoints.

Some personnel are exploiting their positions to rob civilians, further deepening mistrust between the forces and the local population.

According to the organization worker, whose name Enab Baladi withheld, those who seized his belongings spoke with the accent of Syria’s coastal region in the west of the country, where many of those described as “regime remnants” come from.

At night, former regime personnel are deployed at checkpoints in eastern rural Deir Ezzor. Residents interviewed by Enab Baladi in the towns of Hajin (in the Deir Ezzor countryside, east Syria), Abu Hamam, Al Tayyana, Al Shheell, and al-Busayrah reported seeing them at the al-Saytara and al-Sabha checkpoints, as well as along the road to the Conoco field.

Locals noted that these personnel scrutinize identity documents in the same way they used to during the former regime, and stop civilians, which they see as attempts to spread fear in the area.

Abd al-Razzaq, an employee at a civil society organization who preferred not to give his family name, said that most SDF checkpoints in the eastern countryside have become a danger to residents and to those coming from government-held areas, due to strict ID checks and what he described as the “deep-seated resentment” following the regime’s fall.

The fading of the SDF’s emancipatory vision

The alliance with “regime remnants” previously involved in violations, together with growing corruption, places the SDF on a path of “political replication”, according to writer and researcher Abdullah Abdoun, who spoke to Enab Baladi.

He said that converging field and political indicators point to intensive SDF moves to absorb officers and personnel from “remnants of the former regime”, as part of what appears to be a tactical repositioning before entering the implementation phase of the 10 March agreement.

The number of recruits has reached thousands, he added, most of them coming from military formations that were previously stationed in the Syrian Desert, or from individuals who found refuge in the SDF after the recent events on Syria’s coast.

According to Abdoun, some leaks indicate that the SDF has opened a training course in the Mount Abdulaziz area in rural al-Hasakah to incorporate these men into its military structure.

“Inflating” military and political clout

Recruiting officers and soldiers from the former regime’s army may seem, on the surface, like an attempt to expand manpower in preparation for integration into the new Syrian army, but its political implications are deeper, Abdoun argues.

He believes the SDF seeks, through bringing in these “remnants of the regime”, to inflate its military and political presence ahead of negotiations with the Syrian government, so that it can negotiate from a stronger position.

He added that this is a pressure strategy, “wrapped in the language of reorganization”, but in reality an attempt to impose a new status quo on Damascus by creating a heterogeneous military bloc that combines Kurdish cadres with remnants of the old formations.

This trajectory, in his view, cannot be separated from the structural confusion that has marked the SDF project since its inception. It is an entity based on temporary alliances and shifting interests rather than a clear national vision.

Abdoun argued that absorbing “regime remnants” does not reflect any political openness or reconciliation, but rather a shortage of qualified cadres and an attempt to buy loyalties with weapons and salaries.

He pointed out that a similar pattern is visible in southern Syria, where groups linked to the spiritual leader of the Druze community in Suwayda (southern Syria), Sheikh Hikmat al-Hijri, are trying to attract former officers and soldiers.

These simultaneous moves from north to south, he said, raise questions about the role of local actors in recycling old networks of influence under new labels.

From a strategic perspective, Abdoun believes that the phenomenon of recruiting remnants of the former regime reflects the absence of a unified national project and exposes the fragility of entities that seek to fill the vacuum left by the state instead of becoming part of it.

While the Syrian government says it is trying to rebuild its institutions around the principle of a single state, these actors are, in his view, expanding chaos and entrenching division, turning the idea of “national integration” into a slogan rather than a real process.

Abdullah Abdoun

Political writer and researcher

Abdoun said that the Syrian experience over the past years has proven that lasting power is not built by amassing weapons, but by unified decision-making. Any project that bypasses the state or maneuvers at its expense, he added, will ultimately find itself outside the national framework.

Obstacles to implementing the 10 March agreement

On 10 March, Syria’s transitional president, Ahmad al-Sharaa, and SDF commander Mazloum Abdi signed an agreement providing for the integration of the SDF into state institutions, both civilian and military.

Since then, rounds of negotiations have been taking place, in a faltering process both sides describe as positive, yet it has not produced any tangible results on the ground.

Political researcher Bassam al-Suleiman told Enab Baladi in an earlier interview that there are numerous obstacles to the talks, most notably what he described as a “sectarian current” hostile to the Syrian state, adding that such a current cannot integrate into the new state.

Al-Suleiman explained that the main barrier to implementing the agreement is the struggle between currents inside the SDF, noting the presence of a faction aligned with former regime personnel that has a sectarian character.

He revealed that leaders of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), headed by its leader Cemil Bayik, along with two prominent figures, Duran Kalkan and Murat Karayilan, who are from Turkey and are currently based in Sulaymaniyah in Iraq, are seeking to bolster their influence by relying on sectarian currents backed by remnants of the former Assad regime.

Although this current raises secular slogans, it has a “sectarian bent”, al-Suleiman said. The three leaders from Turkey belong to the same sect as former president Bashar al-Assad, which has reinforced the presence of some 5,000 fighters whom the government labels as “regime remnants” inside the SDF, according to the researcher.

In al-Suleiman’s view, the current aim is to obstruct the negotiations and exert pressure on other factions within the SDF that wish to join the Syrian state.

[Source: Enab Baladi]